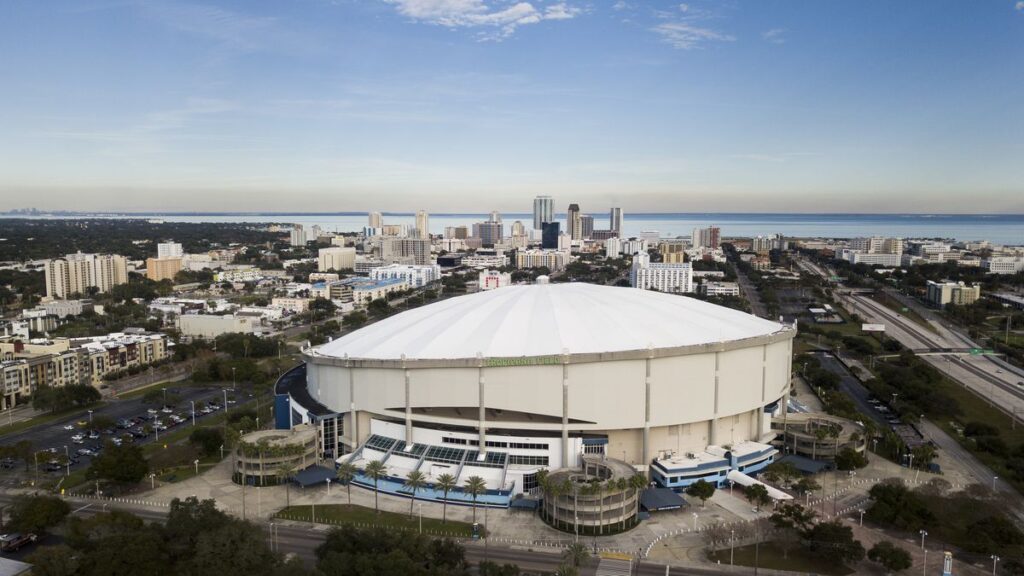

If all goes according to plan, in 30 years time, construction workers will be putting the finishing touches on the final building in an 86-acre redevelopment project that will transform St. Petersburg.

By then, Sunshine City, Florida, surrounded by water on three sides, will exist in a changed world: Sea levels around St. Petersburg could be up to 2 feet higher, and residents could endure five more days of scorching heat each year and eight more days of near-record rainfall.

But only in the final stages of negotiations over the Tampa Bay Rays’ new stadium and the redevelopment of the surrounding Historic Gas Plant District did officials address how environmentally sensitive the $6.5 billion project will be. And when they did, they spoke of lofty goals that were far from a guarantee.

For example, members of the building team said the stadium could generate more solar energy than any other major league ballpark, but contract documents only say the company will “develop a plan” for generating the renewable energy.

Pinellas County commissioners are scheduled to vote Tuesday on whether to use $312.5 million in tourist tax revenue to build the stadium, the project’s final remaining hurdle.

The Suncoast Sierra Club rebuked St. Petersburg City Council members after the bill was approved 5-3 earlier this month.

“The city could have been a leader in securing contractual commitments to build a world-class sustainable and resilient facility, but failed to do so,” the group said in an email.

The contract includes requirements such as restoring and protecting Booker Creek, which runs alongside the stadium, building structures that can withstand Category 4 hurricanes and ensuring there are chargers for electric vehicles, and some environmental groups have expressed support for parts of the plan.

“We want to use the best technology available for the stadium and each phase of the remaining 60 acres,” St. Petersburg Mayor Ken Welch said. Asked how he would evaluate that, Welch pointed to a last-minute change by the City Council to force developers to implement sustainability standards throughout their projects.

Welch also noted that the developer has won environmental awards for other projects.

Adapting to Climate Change

So how prepared are stadium designs for the effects of climate change?

The good news is that much of downtown St. Petersburg is outside of hurricane evacuation zones, meaning the ground beneath the tropical reef is high and dry and will be spared the effects of sea-level rise, which is expected to reach more than two feet by 2050, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s “high” projections.

But as annual temperatures rise, the most deadly weather-related danger — heat — will become a much bigger threat.

Climate experts say the planet is likely to hit a milestone of 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels by 2040.

Spend your days with Hayes

Subscribe to the free Stephinitely newsletter

Columnist Stephanie Hayes will share your thoughts, feelings and funny happenings every Monday.

You’re signed up!

Want to get more of our free weekly newsletters delivered to your inbox? Get started today.

Explore all options

St. Petersburg will see a doubling of the number of days with temperatures above 95 degrees Fahrenheit, according to the Fifth U.S. National Climate Assessment.

Mohit Mehta, global head of sustainability for Populous, the architecture firm designing the new Trop, said the developers are considering the climate. He said there will be at least 1.2 million gallons of rainwater storage, which will be used for cooling towers to “disperse heat” and for landscaping, none of which is specified in the development agreement.

The new stadium, like the current one, will be fully air-conditioned. This is essential to protect spectators from heatstroke, but it’s also a sustainability challenge: cooling a space that will accommodate 30,000 spectators requires a huge amount of energy. This demand raises the question of how the project can avoid contributing to climate change by using up a lot of electricity and increasing carbon dioxide emissions in the process.

The contract states the teams will conduct analyses during the design phase to minimize the stadium’s energy use and greenhouse gas emissions.

This rendering shows the Tampa Bay Rays’ proposed new stadium from the outfield perspective. [ Tampa Bay Rays ]

Minutes before the City Council’s final vote, city officials also added contract language requiring the developer to implement “market-appropriate sustainability standards” throughout the development. The developer said it would make “good faith, commercially reasonable efforts” to build a stadium that achieves Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design certification, known as LEED, but did not require the stadium to obtain that certification.

Buildings are labeled with various levels of certification — certified, silver, gold or platinum — to indicate they follow practices such as installing energy-efficient HVAC systems, electric car chargers or waterless urinals. Founded in the 1990s, the program is widely credited with revolutionizing the building industry, bringing environmental protection into the mainstream and giving developers a coveted nameplate-like prestige.

Bahar Almagani, director of the University of Florida’s sustainability and built environment program, said it’s “a huge thing” for a development of this magnitude to receive certification.

“This is going to have a tremendous impact and benefit to the community within the city and, frankly, the entire state of Florida,” she said.

Mehta and Rays president Matt Silverman said they expect the stadium to approach or meet the silver certification standard, but Rays president Brian Auld said it’s best to be flexible and allow for flexibility depending on the stadium’s unique circumstances.

Timothy Kerrison, a Florida State University professor who wrote a book on stadiums and environmental justice, told The Times that the Rays could come up with a better proposal, citing the Miami Marlins’ LoanDepot Park, the Miami Dolphins’ Hard Rock Stadium and the Orlando Magic’s Amway Center as other Florida sports venues that have achieved gold status, a higher standard than the Rays’ proposal.

There’s also debate over whether the certification goes far enough: The program has come under fire in recent years, including from one of its pioneers, Kansas City architect Bob Berkeville.

“The certification has become, ‘Your building is a little less damaging to the environment than other buildings,'” Berkebill told the news site Bloomberg in 2018. “But it still means there’s a negative impact. I think that’s a failure.”

Oberlin College physics professor John Schofield has reached a similar conclusion. He found that over the years, certified and uncertified buildings made no difference in electricity use. His latest study, which looked at 2016 data from thousands of office buildings, found that certified buildings used about 7% less electricity than non-certified buildings.

“It’s just a small savings,” Schofield said. Given those findings, Trop’s certification commitments “wouldn’t give me the impression that we’re being environmentally conscious,” he added.

Restoring an abandoned stream

Restoring Booker Creek is positioned in the developer’s plans as a crucial focal point for the Historic Gas Plant District.

Florida environmental regulators consider the nearly two-mile-long creek a “polluted” waterway in need of remediation. The 2,000 feet of riverbank adjacent to the stadium is often littered with trash and drips with water on dry days. The creek is barely visible through a mesh network of access roads into the ballpark.

According to the agreement, the new waterway concept will enhance habitat for Florida’s wildlife while improving water quality, controlling flooding downstream and capturing trash that floats along the stream.

A walkable trail will be built around the restored creek, stretching for about three-quarters of a mile, and visitors will be able to sit by the water in tiered seating and shaded pavilions similar to those on the Chicago Riverwalk, said Rob Hutchison, principal at EDSA, the landscape architecture firm leading the restoration project.

The rendering, courtesy of EDSA, the landscape architecture firm leading the Booker Creek restoration project, shows a vision for the currently damaged waterway that runs through the grounds of Tropicana Field. [ Courtesy of EDSA and the Tampa Bay Rays ]

St. Petersburg is expected to experience an increase in annual precipitation and extreme weather events due to global warming and increased moisture trapping in the atmosphere. How are project developers preparing for increased precipitation?

For one, the creek drops 10 to 15 feet in elevation along the Trop property. Its lowest point, the southern end next to the stadium, is at highest risk of flooding, and that’s where developers are targeting new stormwater gardens, or ecological parks that would act “like a sponge,” Hutchison says.

To reduce flood risk, EDSA is considering planting water-friendly native plants such as bald cypress.

Architecture firm EDSA envisions a roughly mile-long walking trail that loops around a restored Booker Creek, according to renderings provided by the firm and the Tampa Bay Rays. [ Courtesy of the Tampa Bay Rays and EDSA ]

Tampa Bay Watch, one of the region’s best-known environmental nonprofits, supports the proposed restoration of Booker Creek — members spotted three river otters just outside the stadium during a walk through the creek earlier this spring — and CEO Dwayne Virgint said he was encouraged by the Rays’ plans to add native plants and tree canopy to provide shade.

“Judging by their approach, we believe the Rays organization recognizes the importance of Booker Creek and its sustainability in the design and development process,” Virgint said in a letter to the St. Petersburg City Council. “They are asking important questions and exploring how best to preserve and characterize Booker Creek as a cultural, environmental and educational asset.”

Suncoast Sierra Club members expressed disappointment in the City Council’s vote and vowed to hold the city accountable.

“We need action, not empty promises and greenwashing,” they signed.