After the first time she hurt me it came to my mind that I

want to go back to the Philippines. But then I thought if I go back to the

Philippines, what will happen to my family? I cannot support them if I’m

back there. But it was too late. Every day madam beat me.

–Maria C.,

migrant domestic worker, Manama, January 2010.

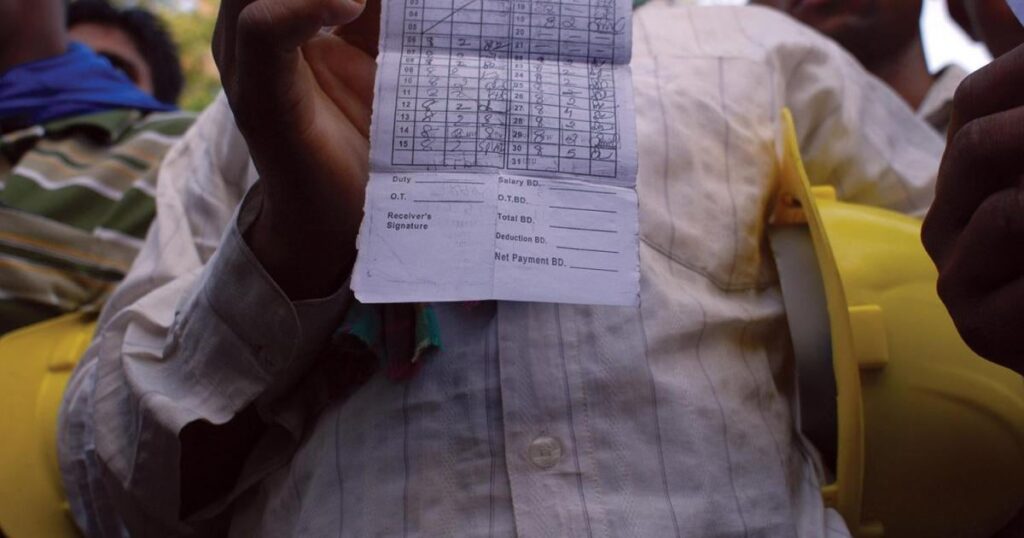

I received only one [full] salary, and for the other months

I got BD27 [$72], but signed for the full amount. The foreman said,

“You’ll get the rest in two days, it’s not a problem, so just

sign it.” When he said that, I signed it.

After working for five months, I asked for my money but

they didn’t give me my money. [The site engineer] told me, “Do your

work; I’m not going to give you money. We’re only going to give you

money for food, BD15 [$40] for 30 days.”

I told him, don’t give me money for food, send me

home—I paid 80,000 rupees [$1705] on my house and I have to give it back.

He said, “There is no money, go to the Labor Ministry, go to the embassy,

you won’t get your money.”

–Sabir

Illhai, migrant construction worker, Manama, February 2010.

For over three decades, millions of workers—mostly

from south and southeast Asian countries such as India, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka,

and the Philippines—have flocked to the Persian Gulf in the hope of

earning better wages and improving the lives of their families back home.

Most of these workers come from impoverished,

poorly-educated backgrounds and work as construction laborers, domestic

workers, masons, waitresses, care givers, and drivers. Providing construction

and service industries with much-needed cheap labor, they have helped fuel

steady economic growth in countries such as Saudi Arabia, the United Arab

Emirates (UAE), Kuwait, Qatar, and Bahrain.

Despite their indispensable contribution to the life of

their Gulf hosts, many workers have experienced human rights and labor rights

abuses, including unpaid and low wages, passport confiscation, restrictions on

their mobility, substandard housing, food deprivation, excessive and forced

work, as well as physical, psychological, and sexual abuse.

The small island nation of Bahrain, with approximately 1.3

million residents, has earned a reputation among labor-receiving countries in

the Gulf as the most committed to improving migrant labor practices. Its

efforts include new safety regulations, measures to combat human trafficking,

workers’ rights education campaigns, and reforms aimed at allowing

migrants to freely leave their jobs. However, questions remain about the

implementation and adequacy of these reforms.

This report explores the experience of Bahrain’s more

than 458,000 migrant workers who make up around 77 percent of the

country’s workforce—most working in unskilled or low-skilled jobs,

in industries such as construction, retail and wholesale and domestic work. The

report traces the many forms of abuse and exploitation to which migrant workers

in Bahrain are subjected by employers and the obstacles and failures that

prevent them from seeking effective redress for such treatment. It outlines the

rights and international legal standards that apply to workers, and calls on

the governments of Bahrain and of labor-sending countries to adopt additional

protections for migrant workers in Bahrain.

Employer and Recruitment Abuses against Migrant

Workers

The plight of many migrant workers in Bahrain begins in

their home countries, where poverty and financial obligations entice them to

seek higher paying jobs abroad. Often, they pay local recruitment agencies fees

equivalent to approximately 10 to 20 months wages in Bahrain, even though

Bahraini law forbids anyone from charging such fees to workers. It is common

for construction and other low-skilled male workers to pay such fees, although

uncommon for domestic workers, who tend to come to Bahrain through formal

recruitment agencies. The debt that many workers incur to pay recruitment

agencies and airfare means they feel compelled to stay in jobs despite unpaid

wages or unsafe housing and worksite conditions for months and even years.

Once in Bahrain, migrants depend on regular payment of their

salaries to meet their own immediate financial needs and those of their

families at home, or to meet monthly loan repayments. Workers indicated that

the problem of unpaid wages tops the list of their grievances. Although

nonpayment of wages is a criminal as well as civil offence in Bahrain, some

employers withhold wages from migrant workers for many months. Without an

income source, migrant workers take on more debt to cover basic needs. In 2008

and 2009 the Individual Complaints Department at the Ministry of Labor received

nearly 1,800 complaints of withheld and late wages. Out of 62 migrant workers

whom Human Rights Watch interviewed, 32 reported that their employers withheld

their wages for between three to ten months: one domestic worker did not

receive wages from her employer for five years. The government did not reply to

Human Rights Watch’s 2012 request for 2010 and 2011 numbers.

On average, migrant workers in Bahrain earn BD205 or $544 a

month, compared to BD698 ($1,853) earned by Bahrainis, and comprise 98 percent

of “low pay” workers (the government defines “low pay”

as less than BD200, or $530, monthly). Most migrant workers interviewed by

Human Rights Watch earned between BD40 and 100 ($106-$265) monthly, while a few

earned up to BD120 ($318) with overtime. The Indian government requires a

monthly salary of at least BD100 ($265) for its nationals in Bahrain, while the

Philippines requires at least BD150 ($398). Employers rarely meet these rates.

The Bahraini government has resisted adopting minimum wage legislation.

Domestic workers earn notably less than migrants in other

sectors, as little as BD35 ($92) per month, averaging BD70 ($186), according to

the government. Many work up to 19-hour days, with minimal breaks and no days

off. Many domestics reported that they were prevented from leaving their

employer’s homes, and some said they received little food. Workers in

other sectors such as construction and service industries generally work 8-hour

days and receive Fridays off, although about a dozen construction workers

reported regularly working 11 to 13-hour days without overtime pay.

Employers typically house construction workers and other

male laborers in dormitory-style accommodation in labor camps that can be

cramped and dilapidated with insufficient sanitation, running water, or other

basic amenities. Three of the four camps that Human Rights Watch visited had

kitchens with kerosene burners, which are fire hazards and violate Bahraini

code. While Bahrain’s Ministry of Labor has worked to improve camps and

make them safer, it has too few inspectors and substandard camps continue to

operate.

Some migrant workers experience physical abuse in the form

of beatings as well as psychological and verbal abuse. There are no reliable

numbers on cases of physical abuse, but 11 of the 62 workers Human Rights Watch

interviewed reported abuse. Over half of these were domestic workers, some of

whom were also subject to sexual abuse and harassment by employers and

recruitment agents, such as unwanted advances, groping, fondling, and rape.

Human Rights Watch interviewed four domestic workers who reported sexual

harassment, assault, or rape by their recruitment agents, employers, or employers’

sons.

Exploited or abused migrant workers often want to change

jobs or return home. Employers almost universally continue to confiscate

migrant employees’ passports upon arrival, even though the practice is

prohibited. Bahraini authorities largely fail to enforce prohibitions on

confiscating passports or compel employers to return the documents. The

Ministry of Labor, immigration officials, and police all say they formally and

informally ask employers to return passports, but they lack the authority to

compel employers who refuse to do so. Workers can appeal to courts, but it can

be difficult to enforce court orders to return passports when employers refuse

to comply. Furthermore, employers must cancel work visas before migrant workers

can leave the country. Senior immigration officials can waive this requirement,

but only do so after repeatedly trying to persuade the employer to cooperate—a

process that can take weeks or even months. Employers also frequently try to

extract payments from employees in exchange for returning their passports and

signing a visa release.

Attacks against Migrant Workers

Migrant workers in Bahrain not only experience abuses within

the context of the employee-employer relationship but also face discrimination

and other abuses from Bahraini society in general. Since 2008, Human Rights

Watch has received reports of assaults on South Asian migrant workers by Arab

men who were not the workers’ employers. For a very brief time in

mid-March 2011, as the confrontation between security forces and anti-government

protesters intensified, these attacks escalated dramatically. The attacks took

place amid growing frustration by many Shia Bahrainis who believe migrant

workers are taking jobs, especially positions with the police and security

forces, away from citizens. Pakistanis, some of whom have been naturalized,

comprise a significant percentage of Bahrain’s riot police.

Human Rights Watch documented several violent attacks

against South Asian migrant workers in and around Manama on March 13-14, 2011,

immediately before security forces launched a violent crackdown on the anti-government

protests. Human Rights Watch spoke with 12 migrant workers who witnessed or

were victims of the attacks, all of them nationals of Pakistan and Bangladesh. Seven

of them said that Arab men armed with sticks, knives, and other weapons

harassed and attacked them at their places of residence. Some alleged that

their attackers were anti-government protesters, though they could not provide

information to support that allegation. All of the men interviewed said they

could not positively identify their attackers because they had covered their

faces with their shirts or masks.

The Bahrain Independent Commission of Inquiry, which

investigated human rights violations in connection with the government response

to anti-government protests, noted that according to Bahrain’s Ministry

of Interior four migrant workers were killed as a result of incidents related

to the unrest and a further 88 expatriates were injured, including 11 Indians,

18 Bangladeshi, 58 Pakistanis, and one Filipino.

Following a criminal investigation by Bahrain’s

Ministry of Interior, authorities prosecuted 15 defendants for their alleged

involvement in the murder of Abdul Malik, one of two migrant workers murdered

in front of a residential building in the Manama neighborhood of Naim. On

October 3, 2011, a special military court convicted and sentenced 14 of them to

life imprisonment. The fifteenth defendant was acquitted of the charges and

released. As of mid-September 2012 their convictions were under review by an

appellate civilian court.

Bahrain’s Reform Efforts

Even before it embarked on recent legal and policy reforms affecting

migrant workers, Bahrain provided legal protections to many migrant workers

that are absent in several neighboring Gulf states. Bahrain’s labor laws

and regulations have long applied to both nationals and to migrant workers

(with the key exception of domestic workers) and include the right of workers

to join trade unions. For example, Bahrain’s 1976 Labor Law for the

Private Sector standardized labor practices, including work hours, time off,

and payment of wages— but failed to protect domestic workers.

Bahrain’s penal code has also provided criminal

sanctions that can protect migrant workers against unpaid wages, and physical

and sexual abuses.

In 2006 Bahrain established the Labor Market Regulatory

Authority (LMRA) with a mandate to regulate, among other things, recruitment

agencies, work visas, and employment transfers. The LMRA’s duties include

issuing work visas, licensing recruiters, and educating workers and employers

about their rights and legal obligations. Its main policy goals include

creating transparency about the labor market and regulations, increasing employment

of Bahraini nationals in the private sector in place of migrant workers, and

reducing the number of migrants working illegally in the country. The agency

has developed an online and mobile phone interface that allows workers to

monitor their work visa status, and produces an informational call-in radio

program that airs on an Indian-language station in Hindi and Malayalam, where

workers can ask questions about their visas and LMRA policies. An

eight-language LMRA information pamphlet distributed to migrant workers upon

entry at the airport tells them how to apply for and change a work visa,

informs them of their right to keep their passports, and provides a Ministry of

Labor contact number to report labor violations.

On April 23, 2012, the National Assembly passed a new

private sector labor law, Law 36/2012, which King Hamad signed into law on July 26, 2012. The new law extends sick days and annual

leave, authorizes compensation equivalent to a year’s salary for unfairly dismissed workers, and increases fines

employers must pay for violations of the labor law. Under the new law,

according to the media, employers who violate health

and safety standards can face jail sentences of up to three months and fines of

BD500 to BD1,000 ($1,326 to $2,652), with punishments doubling for repeat

offenders.

The new law introduces a case management system designed to

streamline adjudication of labor disputes and keep proceedings to around two

months. Lengthy proceedings have until now made it impossible for many migrant

workers to pursue litigation to a final ruling since they were unable to remain

in Bahrain for a lengthy period without a job or income.

According to Bahraini media, Minister

of Labor Jameel Humaidan has said that under the new law domestic

workers “will be entitled [to] a proper labor contract which will specify

the working hours, leave and other benefits.” The government told Human

Rights Watch that the new labor law includes numerous provisions pertaining to

domestic workers.

Most of the law’s protections still do not cover

domestic workers, although some provisions extended to them under the new law do

formalize existing but previously un-codified protections for domestic workers,

such as access to Ministry of Labor mediation, requirement that a domestic

worker have a contract, and exemption from court fees. The law does introduce

new protections as well, including annual vacation and severance pay. However, the

new law does not set maximum daily and weekly work hours for domestic workers

or mandate that employers give them weekly days off or overtime pay. In this

regard, the law fails to address the most common abusive practice of excessive

work hours that domestic workers face.

In June 2012 an official with the LMRA told Human Rights

Watch that the agency had begun drafting a unified contract for domestic

workers that would standardize some protections, but did not provide specifics

of the contract. Ausamah Abdullah Al-Absi, head of the LMRA, told Bahraini

media that the LMRA’s aim was to guarantee decent work and living

conditions for domestic workers and the “unified contract will contain

basic rights of workers according to international treaties.”

Bahraini authorities also moved in recent years to reform

the employment-based immigration system, commonly called the kafala

(sponsorship) system, under which a migrant worker’s employment and

residency in Bahrain is tied to his or her employer, or “sponsor.” In

the past, the sponsor dictated whether a worker could change jobs or leave the

country before the period of the employment contract ended. This gave employers

enormous control over migrant employees, including the ability to force them to

work under abusive conditions. In August 2009, the LMRA reformed the system to allow

migrant workers to change employment without their employer’s consent

after a notice period set in the worker’s employment contract, which

could not exceed three months. Workers then had 30 days to remain in the

country legally while seeking new employment. In June 2011, however, the government watered

down this reform by requiring migrant workers to stay with their employer for

one full year before they can change jobs without employer consent.

Despite the reform of the sponsorship system, the LMRA

continued to reject most applications by migrant workers seeking to change jobs

without employer consent. Employers also continued to have undue influence over

a worker’s freedom of movement because they had to cancel work visas

before migrants could leave the country (unless this requirement was waived by

a senior immigration official). Moreover, the reform fails to cover the

country’s 87,400 domestic workers.

Bahrain took a number of

other steps to address the abuse of migrant workers including:

In November 2006, the Ministry of

Social Development established the 60-bed Dar Al Aman women’s shelter,

with a floor dedicated to migrant women. The facility took in 162 migrant women

in 2008 and 2009—most of whom were referred by police, embassies of

workers’ home countries, and non-governmental organizations (NGOs). The

Ministry of Social Development did not provide 2010 and 2011 numbers in its May

2012 response to Human Rights Watch’s request for updates.

In July 2007, the government implemented a ban on outdoor

construction and other work between noon and 4 p.m. in July and

August—the hottest months of the year. Employers appear to have largely

observed the ban, primarily due to a campaign of sustained inspections by the

Ministry of Labor that demonstrated the government’s ability to enforce

labor standards when it committed resources to doing so.

Law No.1 of 2008 with Respect to Trafficking in Persons allows

the Public Prosecution Office to seek convictions against individuals and

corporations that—through duress, deceit, threat, or abuse of their

authority—transport, recruit, or use workers for purposes of

exploitation, including forced work and servitude. The Bahraini government

understands this law to criminalize many common labor abuses, including

withholding wages and confiscating passports. However, Human Rights Watch found

no evidence that officials have yet used the law to prosecute labor-related

abuses or labor-related human trafficking in Bahrain.

In May 2009, a ban went into effect prohibiting employers from

transporting workers in uncovered open-air trucks, which aimed to reduce

traffic-related deaths and injuries of construction workers and other laborers.

In January 2010, Human Rights Watch observed widespread use of open-air trucks

to transport workers, although in June 2010 we observed noticeably fewer

open-air trucks transporting workers from the same pick-up location we visited

in January. In early 2012 worker advocates acknowledged that the use of these

trucks for transporting workers had become rare.

On December 10, 2010, the Bahraini government released a

report drafted in cooperation with the United Nations Development Programme

(UNDP) on the status of migrant workers. The report included government pledges

to better protect migrant workers from abuse. These pledges came, in part, out

of dialogue between the government and Human Rights Watch in which Human Rights

Watch presented government officials with the findings and recommendations

contained in this report.

Human Rights Watch had recommended that the government

significantly increase the number of inspectors responsible for overseeing

private sector labor, health, and safety practices and, in response, the

government pledged to increase the number of Ministry of Labor inspectors by 50

percent. The ministry in fact increased the number of health and safety

inspectors fivefold, from six in 2010 to 30 in 2011.

Implementation of many of the other pledges, however, has so

far been weak or absent:

The government had pledged to launch an inspections campaign

aimed at “exposing employers who withhold wages and confiscate passports

and to penalize violators.” However, in February 2012 representatives of

the Migrant Workers Protection Society told Human Rights Watch that the

government had not initiated such a campaign and added that the onus remained on

the workers to report complaints to the Ministry of Labor regarding unpaid wages

and to the police regarding confiscated passports.

The government had pledged to initiate a campaign to inform

workers that withholding wages and confiscating passports are crimes under the

anti-trafficking law, to penalize employers that partake in these practices, and

to act on complaints by workers who alleged such abuse. In 2011, however,

authorities had not prosecuted cases of these and other common labor-related

crimes, other than physical and sexual abuse and sex-trafficking. Migrant

rights activists reported that as of February 2012 they were unaware of any workers

rights public education campaigns.

The government had pledged to “consider the adoption of the

… ILO Convention on the treatment of domestic workers.” In June

2011, Bahrain, along with other GCC countries, voted in favor of establishing

the convention, reversing its earlier opposition. As of this writing,

however, Bahrain has yet to ratify the convention, the necessary step to make

it binding.

Government Mechanisms

Addressing Abuses

Labor and criminal courts, and the Ministry of Labor’s

inspections and complaints departments, are designed in part to address worker

grievances and curtail abuses. Human Rights Watch found that abusive and

uncooperative employers often exploit the redress process, delay mediation and

court proceedings, force workers into unfavorable settlements, and avoid

punishment.

The Ministry of Labor had only 33 inspectors in 2010 to

monitor compliance with labor laws and health and safety regulations of over

50,000 companies that employ around 457,500 workers. As noted, the ministry

added at least 24 more inspectors in 2011. The head of the department of

inspections told Human Rights Watch in 2010 that about 100 inspectors would be

needed to conduct just one visit per year to every company. Migrant worker

advocates told Human Rights Watch in February 2012 that the ministry’s

total number of inspectors remains woefully low. Workers in two of the labor

camps that Human Rights Watch visited said that ministry inspectors had cited

their employers for serious housing code violations and ordered one of the

camps to close, but the employer never made the required repairs and, as of

January 2012, the camp that had been ordered to close in fact remained open,

according to local migrant worker advocates. The ministry lacked authority to

penalize companies directly for violations and instead had to forward cases to the

courts, which can impose fines.

Migrant workers may register complaints of labor law or

contractual violations with the Ministry of Labor’s complaints

department, which then calls on the employer to participate in mediation. The

ministry has no authority to compel a settlement, or for that matter employer participation.

Abusive employers often refuse to settle and ignore the ministry’s

request for a meeting. Although the ministry says it resolves about half of all

labor complaints filed by Bahraini and migrant workers, mediation results in

settlements for migrants significantly less often than it does for nationals.

In 2009, 2010, and 2011 Ministry of Labor mediators resolved only 30 percent of

complaints filed by foreign workers, forwarding the rest to labor courts. These

complaints mostly concerned violations of labor law and individual employment

contracts and exclude criminal acts such as assault, sexual assault, or human

trafficking. In all, the Ministry of Labor forwarded 2,321 of these cases to Bahrain’s

labor courts in 2009, 2010, and 2011, involving a total of 3,869 workers.

Labor lawyers and migrant worker advocates often advise migrant

workers to reach a settlement outside labor courts. Lawyers told Human Rights

Watch that courts often render worker-friendly judgments, but that cases take

between six to 12 months to resolve. Labor court trials comprise on average six

separate hearings that take place about every six weeks. Most migrant workers

have no income source during this time, and often feel they have little choice

but to accept an unfavorable out-of-court settlement. Many settle for a plane

ticket home and return of their passports, foregoing a sizable portion, if not

all, of their back wages. Some workers said they had even paid their former

employers simply to return their passports and cancel their visas.

Bahrain’s Public Prosecution Office, which

investigates and prosecutes crimes, has primarily pursued migrant labor cases

that involve physical and sexual abuse. Since passing anti-human trafficking

legislation, Law No.1 of 2008 with Respect to Trafficking in Persons, the

government declared its enforcement a national priority, but thus far the

Public Prosecution Office has only prosecuted trafficking cases that involve

prostitution.

Worker advocates and lawyers complained that authorities can

be unresponsive, and investigations and prosecutions are extremely slow in

criminal and trafficking cases. Advocates shared cases with Human Rights Watch

in which their clients—domestic workers—had suffered severe

physical abuse, and even rape. In one case, the Public Prosecution had not

charged the alleged abuser or completed the investigation more than a year

after the worker filed a police complaint. Authorities soon ended the investigation

altogether. In another case, authorities had not set a trial date more than six

months after the worker filed her complaint and eventually dropped the

investigation.

In a high profile human trafficking case in which 38

construction workers alleged that they were forced to work without

compensation, the first hearing was not called for about three months, by which

time the accused employer managed to persuade most of the complaining workers

to leave Bahrain with promises of small amounts of money and plane tickets

home.

Prosecutions appear to be nonexistent when it comes to

unpaid wages, the most common worker complaint, despite article 302 of the

penal code that criminalizes “unjust withholding of wages.”

Interior and Labor ministry officials appeared to be unaware of this provision

when Human Rights Watch met with them in February 2010. In March 2010, after

that meeting, Attorney General Ali Fadhul Al Buainain issued a decree mandating

criminal investigations and prosecutions in such cases.

Officials in the Ministry of Labor and the Public

Prosecution Office told Human Rights Watch they cannot address abuses unless

the workers themselves come forward to complain. Workers said they faced

obstacles to filing complaints and seeking redress, including a lack of

translators at government agencies, lack of awareness about rights, and lack of

familiarity with the Bahraini labor, immigration, and criminal justice systems.

For example, none of the workers Human Rights Watch spoke with were aware that

they had the right to hold onto their passports. Only one worker knew that he

could transfer employment without his sponsor’s permission. Many workers

did not know where to file complaints. Domestic workers are kept in

employers’ homes and find it particularly difficult to raise complaints.

Bahraini law does not require employers to give domestic workers any time off.

When workers do file grievances, employers often retaliate

with counterclaims alleging the worker committed theft or a similar crime, or

“absconded,” subjecting workers to potential detention in

deportation centers, deportation, and bans on re-entry. Several workers said they

did not lodge an official complaint because they feared an employer’s

retaliation.

In mid-2010, the most recent period for which LMRA figures

are available, some 40,000 migrant workers in Bahrain were working without

proper documentation because their work visas had expired, their sponsoring

employer terminated them, or they left their job (“absconded”)

without permission from a sponsoring employer. Other workers have active work

visas, but work for companies other than the company to which the LMRA issued

their visa, usually a shell company set up to obtain and sell visas. These

so-called “free visa” workers often do not register complaints with

the Ministry of Labor for common abuses like unpaid wages because they fear

deportation, imprisonment, fines, or other penalties.

Bahrain’s International Obligations

Bahrain is a member of the International Labour Organization

(ILO) and has ratified four core ILO conventions, including both conventions

relating to elimination of forced and compulsory labor, and those on the

elimination of discrimination in respect of employment and occupation. Bahrain

also ratified Convention No. 14 (mandating a weekly day of rest for workers in

industries, such as construction), Convention No. 81 (on worksite inspection)

and Convention No. 155 (on occupational health and safety).

Bahrain is a state party to relevant international treaties,

including the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of

Racial Discrimination (CERD), the International Covenant on Economic, Social

and Cultural Rights (ICESCR), the International Covenant on Civil and Political

Rights (ICCPR), the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of

Discrimination against Women (CEDAW), the Convention against Torture and Other

Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CAT), the Protocol to

Prevent, Suppress and Punish Trafficking in Persons, and the Protocol against

the Smuggling of Migrants by Land, Sea and Air.

These treaties obligate Bahrain to protect migrant workers

against most labor-related abuses. Article 7 of the ICESCR recognizes

“the right of everyone to the enjoyment of just and favorable conditions

of work,” including decent wages, safe and healthy working conditions and

rest, leisure, and reasonable limitation of working hours and periodic holidays

with pay. The ICCPR establishes an individual’s right to freedom of

movement, including one’s right to leave any country and enter his own

country. The ICCPR provides for security of person and, along with the CAT, the

right to be free from cruel, inhuman, and degrading treatment, requiring

Bahrain to investigate and punish acts of cruel, inhuman, and degrading treatment

even when committed by private actors. In the Declaration on the Elimination of

Violence against Women, the United Nations General Assembly called on

governments to “prevent, investigate, and in accordance with national

legislation, punish acts of violence against women, whether these acts are

perpetrated by states or by private persons.” A state’s consistent

failure to do so when it does take some attempts to address other forms of

violence, amounts to unequal and discriminatory treatment, and violates the

obligation under CEDAW to guarantee women equal protection under the law.

In its General Comment No. 32, the UN Human Rights

Committee, the body of experts that reviews state compliance with the ICCPR,

declared that under the ICCPR’s article 14 “delays in civil

proceedings that cannot be justified by the complexity of the case or the

behavior of the parties detract from the principle of a fair hearing.”

Furthermore, according to the HRC, article 14 “encompasses the right of

access to the courts,” and that “[t]he right of access to courts

and tribunals and equality before them is not limited to citizens of States

parties, but must also be available to all individuals, regardless of

nationality or statelessness, or whatever their status, [including] migrant

workers….”

During the UN Human Rights Council’s Universal

Periodic Review of Bahrain’s human rights record in 2008 and again in May

2012, the UN Human Rights Council raised concerns about abuses of migrant

workers; in 2007, the committee of experts reviewing Bahrain’s compliance

with the Convention on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW)

concluded that Bahrain should extend national labor protections to domestic

workers; and the Convention for the Elimination of Racial Discrimination (CERD)

committee in 2005 recommended that Bahrain take all necessary measures to

remove obstacles that “prevent the enjoyment of economic, social and

cultural rights by [migrant] workers.”

Although

the government of Bahrain has the primary responsibility to respect, protect,

and fulfill human rights under international law, private companies also have

responsibilities regarding human rights, including

workers’ rights. Consistent with their responsibilities to respect human

rights, all businesses should have adequate policies and procedures in place to

prevent and respond to abuses.

The basic principle that

businesses have a responsibility to respect human rights has achieved wide

international recognition. The UN Human Rights Council resolutions on business

and human rights, UN Global Compact, various multi-stakeholder initiatives in

different sectors and many companies’ own codes of behavior draw from

principles of international human rights law and core labor standards, in

offering guidance to businesses on how to uphold their human rights

responsibilities. For example, the

“Protect, Respect and Remedy” framework and the “Guiding

Principles on Business and Human Rights” for their implementation, which

were endorsed by the UN Human Rights Council in 2008 and 2011, respectively,

reflect the expectation that businesses should respect human rights, avoid

complicity in abuses, and adequately remedy them if they occur.

To the Government of Bahrain

Ensure speedy and full investigation and prosecution of

employers and recruiters who violate provisions of Bahrain’s

criminal laws, including withholding of wages and confiscation of

passports, and impose meaningful penalties on violators.

Ensure that Ministry of Labor mediation and judicial procedures

address labor disputes involving migrant workers in an effective and

timely manner. Ensure that employers who violate the law and regulations

receive meaningful administrative and civil penalties.

Improve the ability of inspectors to address violations of

the labor law and health and safety regulations, including by

substantially increasing the number of inspectors responsible for

overseeing private sector practices.

Extend all legal and regulatory worker protections to

domestic workers, including provisions related to periods of daily and

weekly rest, overtime pay, and employment mobility.

Ratify International Labour Organization Convention No.

189 on decent work for domestic workers.

Mandate payment of all wages into electronic banking

accounts accessible in Bahrain and common sending countries.

Enforce prohibitions against confiscation of

workers’ passports.

Address limitations on freedom of movement for migrant

workers by eliminating the requirement that a sponsor cancel a work permit

before a worker can leave Bahrain freely, and, in cases of abuse and

exploitation, eliminate the requirement that a worker wait one year before

they can change jobs without their employer’s permission.

Take stronger measures to identify, investigate, and

punish recruitment agencies and informal labor brokers who charge workers

illegal fees.

Expand public information campaigns and training programs

to educate migrant workers, including domestic workers, and employers about

Bahraini labor policies, with an emphasis on workers’ rights and

remedies.

Human Rights Watch conducted research for this report in

Bahrain in January, February, and June 2010 with the assistance of Coordination

of Action Research on AIDS and Mobility-Asia (CARAM-Asia), a regional network

of migrant advocate organizations.

Researchers interviewed 62 migrant workers in the greater

Manama area—Bahrain’s capital. These workers were employed in

various sectors including construction, service industries, and domestic work.

Of the 18 who were domestic workers, 15 were living in shelters and three in a

recruitment agency office.

Human Rights Watch also interviewed labor lawyers,

journalists, social workers, worker advocates, union leaders, representatives

of recruitment agencies, and foreign diplomats knowledgeable about the

situation of migrant workers. Four researchers visited two recruitment agency offices,

three construction sites, the government-run women’s shelter, three

shelters run by sending-country embassies, one NGO-run shelter, a judicial

hearing, and four labor camps where migrant workers are housed. They also met

with officials from Bahrain’s Ministries of Labor, Foreign Affairs,

Social Development, Interior, and Justice, as well as representatives of the

Public Prosecution Office and the Labor Market Regulatory Authority (LMRA).

Human Rights Watch followed up these interviews by

submitting detailed questions to the Ministry of Labor, the LMRA, and the

Ministry of Foreign Affairs in March, April, and May 2010, December 2011, and

May 2012. Those letters and the government’s responses are reproduced as

appendices to the Web version of this report.

Human Rights Watch provided the government with our findings

and recommendations and then held a two-day meeting in September 2010 with

representatives of the Ministries of Labor, Foreign Affairs, Interior, Justice,

and the LMRA. This dialogue resulted in the government adopting a set of

pledges, released in December 2010.

Most of the workers interviewed for this report had already

left their employment due to alleged abuses and filed official complaints, and

felt relatively free to tell their stories. Other workers who were still

employed and feared employer retaliation, or were victims of sexual abuse, or

feared deportation because they were working without a valid visa, asked to be

identified by pseudonyms, indicated by use of a first name and initial. Some

experts, including government officials, also asked not to be identified by

name.

In March 2011, while documenting human rights violations in

connection with the government suppression of pro-democracy street protests,

Human Rights Watch interviewed 12 migrant workers in Manama about attacks on

migrants as clashes between anti-government protesters and security forces

intensified. These 12 migrants were not questioned about other issues, such as

conditions of work. When this report refers to “workers who spoke with Human

Rights Watch” or “workers interviewed for this

report”—outside the specific section concerning these attacks—it

is referring to the 62 migrant workers interviewed about labor issues.

In December 2011 and again in May 2012 Human Rights Watch

wrote to Bahraini authorities requesting updated information pertinent to this

report. The government’s response, received on May 28, 2012, is reflected

in the report.

In July 2012 Human Rights Watch wrote to the five

construction companies mentioned by name in the report informing them of the

contents of the report and requesting their response. Two of the companies

responded; their replies have been incorporated into the report and are

reproduced in the appendices to the Web version of the report.

A Note on Terminology

The government of Bahrain does not consider foreigners

working in Bahrain to be “migrant workers,” due to their

term-limited employment contracts and temporary residence in the country. The

government instead uses the terms “contractual workers,”

“expat workers,” or “foreign workers.” Under international

law, the term “migrant worker” refers to a person who is engaged

“in a remunerative activity in a State of which he or she is not a

national.” Accordingly, Human Rights Watch considers foreign nationals

who live and work in Bahrain under term-limited contracts to be migrant workers.

The International Convention on the Protection of the Rights

of All Migrant Workers and Members of Their Families explicitly regards

“seasonal workers,” “project-tied workers,” and

“specified-employment workers,” who earn remuneration as a result

of their activity in a State where they are not a national, as migrant workers.[1]

Although Bahrain is not a party to the convention, this authoritative legal

definition of “migrant worker” applies to the workers whose

situation this report addresses.

Bahrain is a small island nation 25 kilometers off the

eastern coast of Saudi Arabia. About half the country’s resident

population of approximately 1.3 million people are citizens.[2]

The rest are mostly migrant workers. The government puts the number of migrant workers

in Bahrain as of early 2012 at just over 458,000, accounting for about 77

percent of the total workforce.[3]

In 1932 Bahrain became the site of the first commercial oil

discovery in the Persian Gulf. Over the past decade the economy has diversified.[4]

While crude oil production accounts for about 11 to 14 percent of the Gross

Domestic Product (GDP) and 75 percent of government revenue, the country has

emerged as a trading and investment hub, competing with Dubai and its other

Gulf neighbors.[5]

For several decades, Bahrain’s economic development

has largely depended on migrant workers, who can be found in every industry.[6]

Some of these expatriates work in skilled jobs, professions, or middle

management in fields such as finance, education, and import-export companies,

while others run companies and themselves employ and sponsor migrant workers. Roughly

85 percent of the approximately 458,000 migrants who are employed in Bahrain

work in low-wage and low-skilled jobs.[7]

Female migrant workers in Bahrain—about 80,300 in total—tend to be

concentrated in domestic work, with approximately 54,600 women working for

families as cooks, caretakers, and housemaids.[8]Out of

the 377,700 male migrant workers in Bahrain, 115,200, or roughly 31 percent,

are in the construction industry; another 23 percent are in retail and

wholesale trade; 16 percent are in manufacturing; 9 percent in domestic work;

and 7 percent in the hotel-restaurant industry.[9]Additionally,

some 8,200 migrants (male and female) almost two percent of the foreign

workforce, work in the public sector, including in the lower ranks of the

security forces. Another 1 percent work in finance; less than 1 percent work in

education.[10]

By comparison, the country’s workforce contains about

140,100 Bahraini nationals, approximately 34 percent of whom work in the public

sector. The

wholesale and retail trades, manufacturing, construction, and finance combined employ

another 38 percent of all nationals in the workforce.[12]

Bahraini companies and individuals “sponsor”

migrant workers using renewable employment contracts and work visas, mostly for

two years at a time.[13]

Once a work permit expires and is not renewed, the worker (and any accompanying

family members) must leave the country within one month, regardless of how many

years he or she has resided in Bahrain. By law, employers must bear the cost of

the repatriation.[14]

The workers interviewed for this report were recruited from

both rural and urban areas in India, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, Nepal, Ethiopia,

Bangladesh, Indonesia, and the Philippines. Both male and female, their ages

ranged between 20 and 48 years old. Most non-domestic workers paid fees ranging

from US$750 to US$2,000 to recruitment agencies in their home countries to

obtain employment contracts, Bahraini work visas, and airline tickets.

Once in Bahrain, these migrant workers earned monthly wages

ranging from about 40 to 120 Bahraini dinars (BD), equivalent to US$106-US$318.

Construction workers interviewed by Human Rights Watch earned between BD60 and

BD100 ($159-$265) a month, while a few earned up to BD120 ($318) with overtime.

The average monthly construction industry income for male migrants is BD103 ($273)

(which factors in management and skilled workers as well as low and unskilled

workers).

The industry average for domestic workers is BD70 ($186) a month.

Domestic workers interviewed by Human Rights Watch earned between BD40 and BD80

($106-US$212) a month. Worker advocates reported monthly wages to be as low as

BD35 ($93).[17]

Many aspects of migrant workers’ lives in Bahrain are

closely controlled by their employers. Employers typically house their workers.Construction workers stay in dormitory-style

dwellings or labor camps, where employers provide transportation to work and

sometimes meals. Workers in manufacturing, retail, and other non-domestic

sectors might live in labor camps or group apartments that their employer

supplies, and for which they pay rent.

Domestic workers, about 87,400 in total, live in their

employer’s home and rely on their sponsor for food and other daily needs.

They perform tasks such as cleaning, cooking and serving meals, washing and

ironing clothes, shopping, and caring for children and elderly family members.

Employers exercise enormous power over domestic workers’ lives due to the

fact that domestic workers live and work in their homes. Under the sponsorship

system, employers dictate whether domestic workers may leave their employment

for another employer in Bahrain, or must return to their country of origin.

Legally, domestic workers are excluded from many of Bahrain’s labor

protections and inspection mechanisms. Many Bahraini employers view themselves

as the guardians of their domestic workers.

Bahrain’s system of employment-based immigration,

commonly called the kafala (sponsorship) system, exacerbates abuses

faced by migrants and impedes their freedom of movement. Under the kafala system,

a migrant worker’s employment and residency in Bahrain is tied to their

employer, or “sponsor.” In a meeting with Human Rights Watch, Dr.

Majeed Al Alawi, then minister of labor, stated that “the kafala

system is near slavery.”[21]

Employers unduly influence a worker’s freedom of

movement because they must cancel work visas before migrants can quit their job

and leave the country (unless this requirement is waived by a senior

immigration official). Until August 2009, employers also dictated if a worker

could change jobs within Bahrain before the employment contract ended. The

system gave employers enormous control over migrant employees and allowed

employers to force migrant workers to continue working in abusive conditions.

Now workers can change jobs without their employer’s consent so long as

they have been with that employer for at least a year.

In recent years, the plight of migrant workers in Bahrain,

as elsewhere in the region, has received increasing attention. Bahraini and

regional media, particularly English-language publications, have provided

coverage of migrant worker grievances. Hardly a day passes without a media outlet

recounting a tale of abuse and exploitation of migrant workers.[23]

Numerous worker strikes and demonstrations—mainly in

the construction industry and sometimes involving thousands of

workers—have raised public awareness regarding the scale of grievances in

Bahrain.[24]

“Most of the strikes happen when workers are not happy about the living

conditions, non-payment of salaries or low wages,” said Salman Al

Mahfoodh, secretary-general of the General Federation of Bahrain Trade Unions

(GFBTU), the country’s sole trade union federation.[25]

Bahrain is one of the few Gulf States that allow migrant workers to join

unions, although membership remains rather low.[26]

The GFBTU has nonetheless helped migrant workers stage strikes, and migrants

have also organized independently—including a strike involving some 5,000

workers against the al-Hamad construction company, in which the workers

recovered several months of back wages.[27]

Bahraini civil society organizations, unregistered migrant

worker associations, human rights organizations, expatriate cultural

organizations, and the GFBTU have also served as sources of advocacy and

information, particularly the Migrant Workers Protection Society,

Bahrain’s leading migrant rights NGO. Some foreign embassies have also

stepped up advocacy on behalf of their nationals by meeting with the Ministry

of Labor, providing lawyers and other resources for aggrieved workers, and

opening shelters for domestic workers.

Internationally, United Nations human rights bodies have

highlighted the treatment of migrant workers in Bahrain. UN Human Rights

Council member states raised the issue of migrant worker rights during Bahrain’s

2008 and 2012 Universal Periodic Review (UPR).[28] In 2007, the UN Committee

on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women expressed concern with

“the poor working conditions of female migrant domestic workers.”[29]

The committee called upon Bahrain “to take all appropriate measures to

expedite the adoption of the draft labor [law], and to ensure that it covers

all migrant domestic workers,” and “to strengthen its efforts to

ensure that migrant domestic workers have adequate legal protection, are aware

of their rights and have access to legal aid.”[30]

The UN Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination in 2005

recommended that Bahrain take all necessary measures to extend full protection

from racial discrimination to all migrant workers and “remove obstacles

that prevent the enjoyment of economic, social, and cultural rights by

[migrant] workers.”[31]

Recruitment Process

Recruitment of migrant workers to Bahrain takes two forms.

The first involves recruitment companies in sending countries working on behalf

of, or in coordination with, Bahrain-based recruitment agencies that local

employers pay to find workers.[32]

This arrangement is the norm for domestic worker recruitment, but is also used

in other sectors.

The second practice, common in the construction sector and

other non-domestic low-income sectors, involves a migrant worker finding

employment through an informal middleman— often a friend, family member,

or acquaintance already in Bahrain. Sometimes Bahraini employers approach these

middlemen and ask if they know anyone who wants a job. Sometimes would-be

migrant workers ask their contacts in Bahrain to find them a job. One

Manama-based document clearance agent, responsible for submitting work visa

applications for Bahraini companies, explained:

The normal way is that the worker there back home tells his

friends to find a job for him. Maybe more than 80 percent is like this. Then

the friends living outside start speaking to the people, “Find a job for

my nephew, for my cousin, for my brother.” It’s depending on the

person, how active he is, and how connected he is.[33]

Bahrain’s Law No. 19 (2006), entitled Regulating the

Labor Market, permits only persons licensed by the Labor Market Regulatory

Authority (LMRA) to “carry out the business of a recruitment agency or

employment office.”[34]

This applies to employers who directly recruit migrant workers, as well as to

those companies that act as intermediaries in the recruitment process.[35]

Prior to 2006, recruiters required a license from the Ministry of Labor.[36]

Under the law, employers must pay certain fees to the

government for each foreign worker they recruit into the country. These charges

include a fee for work visas and residence permits totaling over BD220 (US$584).

In addition, employers pay recruiters, fixers, and document clearance agents

service fees, and provide workers with airline tickets to travel from their

home countries to Bahrain.[38]

The LMRA also used to charge employers BD10 ($27) per month per migrant worker.

This fee was designed to raise the cost of hiring foreign workers, making

Bahraini labor more competitive in the market.[39] Starting in April

2011, the LMRA suspended the fee, following intense lobbying by employers and

in the context of a far-reaching campaign of repression against pro-democracy

protests that some cited as crippling the economy.

Prime Minister Khalifa bin Salman Al Khalifa ordered a freeze on the 10 BD fee

until June 31, 2012 and on July 6, 2012 the government announced the freeze

would be extended until the end of the year.

Bahraini law explicitly forbids Bahraini recruiters from

collecting any of these fees and travel costs from prospective migrant workers.[42]

Officials with licensed and regulated recruitment agencies that place the

domestic workers told Human Rights Watch that they generally complied with this

law. However, when it comes to construction and other sectors, some recruitment

agents and employers appear to openly flout the prohibition by requiring that

prospective workers reimburse them for these fees.

For workers in construction, manufacturing, and other

non-domestic sectors, Bahraini sponsors or informal recruiters commonly solicit

agencies located in sending countries to handle the visa applications of

would-be migrant workers. These local agents compel workers to bear travel and

other costs. A Manama-based document-clearance agent told Human Rights Watch

that recruitment agencies or employers often have an office liaison in sending

countries. The agent added:

As per the rule, all tickets have to be paid by the

sponsor, [but] usually [the workers] pay for the visa and for the ticket. But

this is all under the table— officially nobody pays any money and nobody

takes any money [but] normally the agency has a placement fee, and it’s

two months’ salary, and then they charge the sponsor also here, which

they call recruitment fees. No way is this done officially, and if the sponsor

takes money then the [worker] can go to court and say this person has taken the

money.[43]

All but one of the 44 male workers Human Rights Watch

interviewed had the same experience of being required to pay up-front sums

ranging from $750 to $2,000 to their recruiting agents in exchange for work

visas and airline tickets. These fees are equivalent to approximately 10 to 20

months of most migrant workers’ wages in Bahrain.

Muhammad Rizvi Muhammad Siddeek, a 38-year-old Sri Lankan

driver, told Human Rights Watch he had come to Bahrain to earn enough money to

pay for surgery for his father and young son:

I paid money to an agent named Ali Zamir Employment Agency

in Katunayake area near my house in Sri Lanka. I told him I needed a job as a

driver. He said, I will get you a Bahraini visa and send you. I paid 83,000

[Sri Lankan] rupees [US$729]. I sold my wife’s gold for the money.[44]

Sabir Illahi is a 33-year-old mason from Rajasthan, India,

who had never left his home country before coming to Bahrain in early 2009. He

said:

I knew a man from Rajasthan [already in Bahrain]. He got my

visa. I paid 80,000 rupees [$1,725] for the visa. [To get the money] I gave the

papers to my land to a man [in India].

In Rajasthan, I got my visa from a relative. The engineer

of the company here [in Bahrain] sent the visa to him, that man gave the visa

to me. I gave him 80,000 rupees, and I got a ticket to come here, and a visa.[45]

Purveen G., one of 13 men from India working as a laborer

for a major construction firm, summarized their experience:

We all came through an agent, paying 50,000-60,000 rupees

[$1,300-$1,355] in India. This cost covered all expenses. We came directly to

the company once in Bahrain. Some of us mortgaged our properties, lands and

homes, with interest.[46]

Domestic workers whom Human Rights Watch spoke with seldom

had to pay the fees that other low-income migrant workers did. Instead,

industry practice is for the sponsoring family to cover expenses associated

with recruitment, including visa costs, air travel, and an additional payment

to a Bahraini recruitment agency.[47]

Nonetheless, in some cases recruiters in sending countries do force domestic

workers to pay fees. Fareed al-Mahmeed, chairman of the Bahrain Recruiters Society,

told Human Rights Watch that it was not uncommon for recruiters to charge

domestic workers fees in their home country.[48] Maria C., a

migrant domestic worker from the Philippines, told Human Rights Watch:

There was a recruiter who came to my house and offered me

and my family [a chance for me] to come to Bahrain. She said I would earn a lot

of money if I came here—money that I could use to support my family. She

asked me to pay her for my visa fee, my employment fee, [and] other fees before

I leave the Philippines. We paid 35,000 [Philippine pesos, or $756] in the

Philippines. [To raise the money] we sold our motorcycle. Then I came to

Bahrain. My sponsor picked me up from the airport and I signed a contract at my

sponsor’s house.[49]

While it is illegal under Bahraini law to force workers to

pay recruitment fees or to cover the cost of visas and travel, a study

conducted by the LMRA found that 70 percent of migrant workers secured jobs in

Bahrain by borrowing money or selling property in their home countries.[50]

Fee payments and debt contribute to an exploitative employer-employee

relationship. Workers who arrive with sizable debts—like Suresh Podar, a

laborer from Nepal—are less likely to feel they can complain or leave

exploitative work conditions for fear of losing their jobs and the right to

remain legally in Bahrain. Suresh, who came to Bahrain on his cousin’s

recommendation, said:

My relative was already in Bahrain working on my

sponsor’s boat and got me a job. My relative knew an agent in Nepal who

arranged everything. We gave him 30,000 Nepalese rupees [$425] and gave [BD]

200 [$531] to my sponsor when we got here. I wasn’t told I’d also

have to pay my sponsor. I was told I’d work in a garage as a helper but

when he got here we were told to work on a fishing boat. I can’t swim and

didn’t want to work on a boat. But since I already paid so much money to

get here I decided to stick with it.[51]

Making matters worse, some workers raise money at home for

the visa fees and travel by borrowing at exorbitant interest rates, sometimes

using family valuables or property as collateral. Suresh recalled:

I had borrowed the money from my brother. My brother had to

borrow the 30,000 [rupees, $425] from someone else and my brother has to pay

interest. I pay my brother. [After about two years] I have paid back 20,000

[$283] out of 30,000, but I still need to pay back another 40,000 [$567], so

60,000 [$850] total.[52]

Sant Kumar, Suresh’s cousin, said he had to pay

interest and offer collateral.

On average, for every thousand [Nepalese rupees, $14] I

borrowed I have to pay back about 1,300 [$18]. I borrowed 30,000 from one

[lender] and 30,000 from another. I put my house up for collateral. It’s

my own house so I don’t pay rent but if I don’t pay what I owe they

will take my house.[53]

Passport Confiscation and Mobility

Bahraini law prohibits employers from confiscating their

employees’ passports. The government has explained that the practice is

criminalized under the anti-human trafficking law and article 389 of the penal

code, but employers continue to routinely confiscate their employees’

passports, typically retaining them for the duration of employment.

All 62 workers interviewed by Human Rights Watch said their

employers had confiscated their passports on arrival in Bahrain. In 2008 and

2009, the Ministry of Labor’s Individual Complaints Department received

1,583 complaints from workers seeking their passports.[55]

Moham Kumar, India’s ambassador to Bahrain, observed that most cases of

passport confiscation take place at what he called “smaller companies.”

By withholding workers’ passports, employers exercise

an unreasonable degree of control over their workers and create significant

impediments to a worker’s ability to leave his or her abusive employer,

or return to his or her home country.

Rules governing how employers “sponsor” workers

and work visas exacerbate this problem. A worker who wants to return home not

only needs to repossess his or her passport, but also to secure the

employer’s agreement to cancel the employment visa. Migrant workers

unable to meet these official requirements for leaving the country risk

penalties for violating local immigration laws, including detention and

deportation.

Eight workers reported that their employers asked them for

money in exchange for returning their passports and canceling their work

visas—a common practice according to an immigration officer.[57]

Bahrain media reported similar stories of workers being asked to pay employers

before they received their passports.[58]Two workers interviewed by Human Rights Watch who filed complaints with

the minister of labor and labor courts became frustrated by the ineffectiveness

of the government’s remedial process and eventually agreed to pay their

employer in order to leave Bahrain.[59]Another four workers reported that their employers asked them for money

before cancelling their work permits so they could move to new jobs.[60]

After arriving in Bahrain from Bangladesh, Mukhtar Mojibur

Rehman learned there was no job waiting for him, even though he had a valid

work visa.[61]

Mukhtar’s recruiter told him that authorities would deport him if he

reported the recruitment fraud. Having paid fees to come to Bahrain, Mukhtar

spent several months trying to secure employment and worked odd jobs, including

a four-month stint as a vegetable gardener for which he was not paid.

Frustrated by his lack of steady employment and income, he decided to return

home.

I called up this guy who set up the visa and I told him,

okay, fine, I’ll go back. He said the sponsor wanted 500 dinar [$1326],

[he] won’t let you go unless you pay him. I told the man that I would pay

the 500 dinars. But then he said, “No, your sponsor 1722184809 wants

1000.”

I don’t know if my sponsor or my employer has my

passport. So, I know I need an out-pass.[62]

An out-pass is a one-time travel document issued by the

relevant embassy or consulate allowing a worker to leave Bahrain and return to

his country of origin. Migrant workers frequently must apply for out-passes

after failing to retrieve their passports. Mukhtar Mojibur Rehman described his

experience to Human Rights Watch:

I’ve been trying to get an out-pass. I went to the

Bangladeshi embassy two months ago to get an out-pass and they told me to come

back after two days. Two days later they told me there are 1,200 people

who’ve applied. [Three days ago] they told me there’s 200 left

[waiting ahead of me]. Once their papers are processed, yours will be done.[63]

Like Rehman, dozens of workers told Human Rights Watch how

they wanted to leave their employment and return home, often after experiencing

abuse or extended periods of nonpayment. None were able to retrieve their

passports and return home without help or paying off their employer. Most

workers tried to seek government assistance to retrieve their passports, a

process that can take between several weeks and several months, with mixed

results. Most who eventually left the country did so on an out-pass.

Immigration and Ministry of Labor officials do not have any

power to force employers to return passports.[64] Neither do the

police, at least not without a court order. Beverley Hamadeh of the Migrant

Workers Protection Society described what happens when workers appeal to the

courts to get their passports back.

Court orders are sometimes used to enforce the return by

the employer of the illegally held passport to the employee. The employer may

return [the passport], but fail to cancel the visa, which is critical for the

repatriation process. This often also occurs when the [Ministry of Labor] arbitrator

agrees with the employer to return the passport.[65]

Attorney Maha Jaber told Human Rights Watch that she had

secured orders for the return of her clients’ passports from

Bahrain’s Urgent Matters court. “It could take three to four weeks,

but as soon as I have a judgment we execute it through [appealing to the]

execution court,” she said.[66]

The government told Human Rights Watch that passport

confiscation is criminalized under the penal code’s article 389 and the

anti-human trafficking law.

Penal code article 389 specifically prohibits acquiring a

document by “force or threat.”

Nearly every workers interviewed by Human Rights Watch said that they had given

their employer their passport because the employer told them to, or told them

it was standard practice. All these workers said they were unaware that it was

illegal for an employer to confiscate their passports. It remains unclear

whether these types of cases are prohibited under the penal code’s

“force or threat” requirement.

Bahrain’s human trafficking law also provides criminal

sanctions for labor-related “exploitation” similar to forced labor.

Brig. Tariq Mubarak Bin Daineh, then undersecretary of the Ministry of

Interior, explained that it “is not [explicitly] in the human trafficking

law that holding the passport is a crime, but there is a trend now between the

police and the Public Prosecution to treat this as [the crime of] human

trafficking.”[70]

However, when asked about the criminality of withholding passports, Attorney

General Al Buainian told Human Rights Watch that the Public Prosecution had yet

to determine if confiscating a passport and withholding it was a crime or an

act of human trafficking—even when coupled with extensive withholding of

wages by the employer.[71]

Advocates with the Migrant Workers Protection

Society’s Action Committee said they were unaware of any employer being

punished for withholding a passport.[72]

When pressed by Human Rights Watch, officials in the Ministry of Labor,

Ministry of Interior, and Public Prosecution Office could not give any example

of punitive measures, criminal or administrative, taken against employers who

withheld passports. Nadia Khalil al-Qaheri, head of the Labor Complaints

Section at the Ministry of Labor, told Human Rights Watch that all her department

could do was either request the employer to return the passport or refer a

worker to seek assistance through the Ministry of Interior or the courts.[73]

Lt. Col. Ghazi Saleh al-Senan, director of Follow Up and Investigation at the

General Directorate of Nationality, Passport and Residence (i.e.,

Bahrain’s immigration directorate) in the Ministry of Interior, said that

when his office gets involved, employers either return the passport or claim

not to have it.[74]

One immigration officer who deals directly with these cases

told Human Rights Watch that he can only request—rather than

compel—employers to return the passport and release the visa.[75]

He calls the employers twice and then sends a summons via the police to appear

at immigration. If the employer ignores the officer’s requests after

three attempts—which the officer indicated sometimes happens—or

refuses to agree to release the work visa, the officer submits a written report

to a senior immigration officer, who is empowered to waive the visa cancellation.

But the waiver process takes weeks, even months, and workers still need to

either seek their passport through the courts or apply for an out-pass.

Lt. Col. al-Senan told Human Rights Watch that employers

“do not have the right to take passports.” He explained that if the

immigration officers receive complaints of confiscation, “We contact [the

employer] and ask him to return the passport.” He discounted the problems

this practice raises, saying, “The passport with the sponsor is nothing,

not an issue. If he wants to leave the country or transfer to another sponsor

the passport is not needed.”[76]

Contrary to Lt. Col. al-Senan’s dismissive comment,

passports remain vital documents that workers need, not only to leave the

country freely, but also to secure valid employment and residency in Bahrain.

The only way workers can leave employers and legally stay in Bahrain is by

changing employers. Starting in August 1, 2009, migrant workers in

Bahrain—except for domestic workers—could freely change jobs

through the LMRA without their employers’ consent. Ali Ahmed Radhi, then chief

executive officer at the LMRA, told Human Rights Watch that all LMRA services,

including employment transfers, could be done without passports using various

identification methods, even fingerprints. According to Radhi:

Provided that information regarding the foreign worker is

already in the LMRA database, the LMRA does not require the employer who is

applying for the new work visa to produce the original passport; a copy of the

passport would suffice for the purpose of applying for a new work visa.

He added that:

After the issuance of the work visa, the foreign worker

will eventually be required to produce his passport, not to the LMRA, but to

[immigration officials] for the issuance of the residence permit.[77]

However, several members of the Migrant Workers Protection

Society, as well as other migrant worker advocates, told Human Rights Watch

that they have difficulty accessing any LMRA or immigration services for a

worker without his or her passport.[78]

They also said that attaining a waiver of a visa cancellation can be complex

and time-consuming. Advocates complained of a disconnect between the simple

process described by top government officials and the bureaucratic obstacles

they encounter in reality when seeking assistance for their clients. Marietta

Dias observed:

If you go talk to the ministers and look at the law

everything is perfect and nothing can’t be handled. But when you go to

the little guys [in the ministries], the guys that process everything, they

either don’t have the authority to do anything or they haven’t been

told the law.[79]

Unpaid Wages

One of the main complaints that migrant workers voiced to

Human Rights Watch was that their employer failed to pay their wages in full or

on time. Unpaid wages are the most common issue in labor disputes mediated by

the Ministry of Labor, and a frequent reason for workers leaving employment.[80]

Media reports and migrant labor advocates suggested the international credit

crunch starting in 2008 may have exacerbated the problem.[81]

In April 2012, Indian Ambassador Moham Kumar told the independent daily Al-Wasat

that the largest issue currently facing Indian workers was non-payment of wages

for periods of several months, which he attributed to a struggling economy.

The Individual Complaints Department at the Ministry of

Labor, which mediates labor disputes between employers and employees, received

227 complaints of withheld and late wages in 2007, 792 complaints in 2008, 987

complaints in 2009, and 356 complaints in the first quarter of 2010, the most

recent figures available to Human Rights Watch.[83] The

government failed to reply to Human Rights Watch’s requests for 2010 and

2011 numbers. The Ministry of Labor also houses a department of inspections

that is charged with monitoring compliance with Bahrain’s labor law and

health and safety standards. This department, which mainly gets involved in situations

of large-scale non-payment of wages, received nine complaints specifically

regarding unpaid or late wages, out of a total of 203 complaints in 2008.[84]

In 2009, the number of complaints of unpaid or late wages that the department

of inspections received rose significantly to 140 out of a total of 371

complaints.[85]

Just over half of the migrant workers interviewed by Human

Rights Watch said that their employer had withheld their wages. This complaint

was especially common among construction workers. All of these workers were

still owed back wages when they were interviewed. Their employers had not paid

them any wages for between three and ten months. One domestic worker had not

been paid in five years. In a few cases, workers received a full or partial

monthly wage in the midst of extended periods of non-payment. [86]

Withholding wages violates the Bahraini labor law and is

also a crime under the penal code.[87]

Moreover, the impact on workers whose wages are withheld for even one month is

very serious: they immediately fall into arrears on debt they owe in their home

countries; they can incur additional interest; and they are unable to send

money home to their families, which depend on the income earned in Bahrain.

Unpaid workers must often run tabs at local stores or borrow additional money

from friends just to buy food and necessities.

Acihi binti Mahid, a domestic worker from Indonesia, worked

for her sponsor in a two-story house in the al-Budaiya suburb of Manama.

“I cleaned, cooked, and took care of three babies. I expected that the

sponsor could pay the salary,” Mahid told Human Rights Watch.[88]

Instead, she went unpaid for the entire seven months she worked for the

employer.

I was supposed to be paid 70 dinars [$186] as promised by

an agent in Indonesia. I expected to receive money from the sponsor every

month. I asked the sponsor for my pay so many times. He said, if you want to

send the money to Indonesia I’ll to give it to you … I asked so

many times but never got it. I need to send money to my family. I send it to my

father. My parents take care of my nine-year-old daughter.[89]

Lawrence Sarwan Singh, a 37-year-old tile mason, left his

parents, sister, wife, two sons, and a daughter in Mumbai to work for a

Bahraini manpower agency that supplies workers for building projects. Singh

told Human Rights Watch:

I was one of 46 men working for a supply company. We were