WASHINGTON (AP) — As she inches closer to winning the Democratic presidential nomination, a key question is emerging for Vice President Kamala Harris: whether she can translate the Biden-Harris administration’s economic record to political advantage in a way that President Joe Biden couldn’t.

In some ways, her task seems easy: Her administration has overseen a strong recovery from the pandemic recession, lowering the U.S. unemployment rate to a half-century low of 3.4% in early 2023, well below the harrowing 6.4% it was at when Biden and Harris took office in 2021. The unemployment rate has remained below 4% for more than two years, the longest such streak since the 1960s.

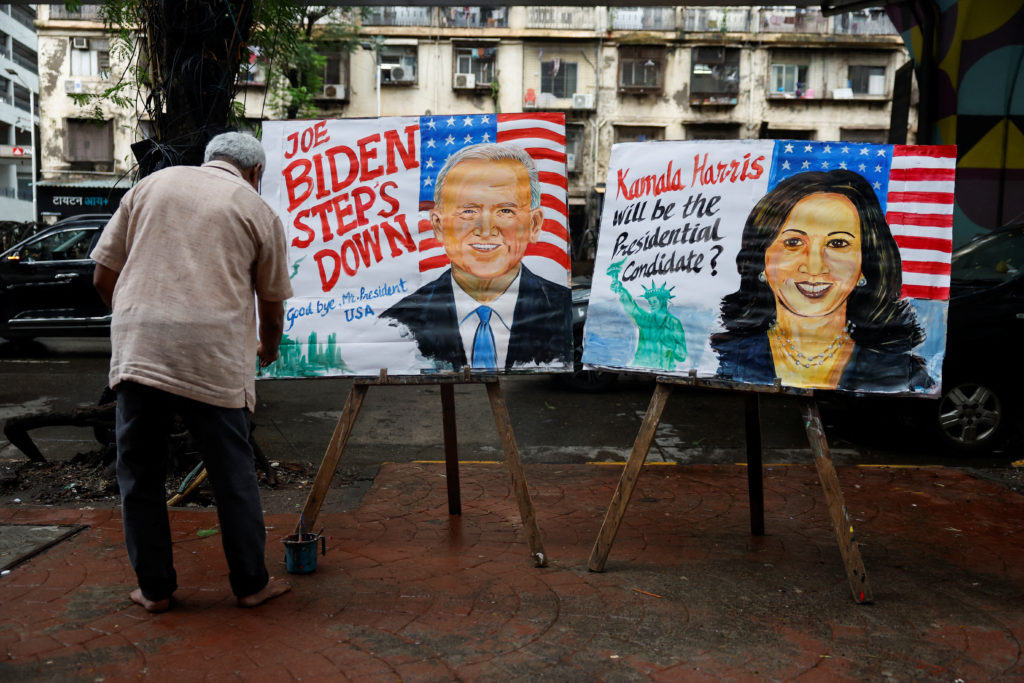

WATCH: Harris wins support from key voting bloc as Trump shifts strategy after Biden drops out

Strong economic growth, fueled by the administration’s $1.9 trillion stimulus package, has created a surge in demand for workers, forcing employers to raise wages, with pay for low-wage workers especially soaring and narrowing income inequality.

However, the administration’s economic stimulus package led to a surge in demand for furniture, automobiles, and other items, and supply chains were clogged, quickly resulting in parts shortages. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine caused gasoline and food prices to soar. In June 2022, inflation hit its highest level in 40 years.

The price surge was so severe that it erased most of the wage gains workers had been enjoying, and it made Americans more dissatisfied with the economy. Consumer confidence plummeted in the second half of 2021 and has barely recovered, even as inflation plummeted from 9.1% to 3% in 2022.

The gloomy view of the economy is at odds with the generally positive data on employment, falling inflation and economic growth. Chris Jackson, director of polling at Ipsos Public Affairs, attributes this to a cumulative average price rise over the past three years (about 20 percent, only partially offset by wage increases) and general anxiety about the direction of the country.

“People, generally speaking, are doing well,” Jackson said. “They have jobs, they get paychecks, they’re getting raises, all that stuff. But they feel like the money isn’t doing them much good. They feel like the country in general isn’t going in a good direction.”

Former President Donald Trump has spoken out about the rising cost of living, mentioning inflation 14 times in his speech at the Republican National Convention last week. Trump’s running mate, Sen. J.D. Vance of Ohio, has accused Biden of allowing high housing costs to dampen the aspirations of many would-be homebuyers.

Speaking in Indianapolis this week, Harris touted her support for “affordable health care” and “affordable child care” and also criticized Trump for eliminating the Biden administration’s insulin price cap, which the White House frequently cites as an example of efforts to reduce high drug costs.

Read more: Harris says she’s ‘open to debate’ Trump, accuses him of backing out of Sept. 10 showdown

While inflation has slowed significantly over the past two years, Americans remain frustrated that average prices are still much higher than they were just a few years ago: Grocery prices have risen 21% since Biden and Harris took office. The average apartment rent has risen about 23%, to $1,411 a month, according to Apartment List.

And to fight inflation, the Federal Reserve, under Chairman Jerome Powell, has raised its key interest rate at the fastest pace in four decades. As a result, borrowing costs have soared: The average rate on a 30-year fixed mortgage has more than doubled from a pandemic low of about 2.7% to about 6.8% last week.

The combined rise in price increases and inflation was especially shocking for many families because it occurred after nearly a decade of almost no inflation and ultra-low interest rates. American households had become accustomed to barely any price increases. For example, U.S. food prices remained essentially flat from 2015 until the pandemic. When high inflation eventually hit, Americans’ finances took a hit and their economic outlook became bleak.

Still, many leading policymakers see the Fed’s rapid rate hikes and subsequent fall in inflation as an economic success story. When the Fed raised interest rates aggressively, sharply raising the cost of lending for consumers and businesses, fears spread that the U.S. could soon slip into a recession. In August 2022, Chairman Powell issued a high-profile warning that the Fed’s inflation efforts would “cause pain for households and businesses.”

Instead, inflation has been falling without a spike, the unemployment rate remains low at 4.1%, and Fed officials have signaled they are becoming increasingly confident that inflation is falling steadily toward their 2% target.

Christopher Waller, a ranking member of the Federal Reserve Board, praised the progress in remarks last week.

“We’ve never seen anything like this before in terms of severe policy tightening,” Waller said of the Fed’s rate hikes. “The economy is holding up, inflation has come down substantially. This is a remarkable recovery compared to what’s happened in ’21 and ’22.”

But many ordinary Americans, still struggling with high costs, don’t share the enthusiasm. New car prices, for example, have risen 24% in the three years since the pandemic began, to an average of $48,000. New car prices have remained roughly stable over the past year, according to government data. But General Motors said Thursday that customers paid about $50,000 on average for one of its new vehicles in the April-June quarter.

Perhaps most damaging, housing affordability has worsened. Home prices and mortgage rates are both much higher than they were three years ago. Monthly payments on the median-priced new home have jumped by nearly a third over that time to more than $3,000, according to the Joint Center for Housing Studies at Harvard University. Potential homebuyers need to earn at least $100,000 to purchase a median-priced home in nearly half of metropolitan areas, according to the center’s research.

Abigail Wozniak, director of the Opportunity and Growth Institute at the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis, said the burden of such large purchases becomes more difficult to manage when overall prices soar.

“It’s hard to make small, immediate changes to your spending on cars and homes,” Wozniak said. “You’re forced to think about big budget choices like whether it’s better to give up your car and switch to public transportation. It’s a big adjustment. And adjustments are painful.”

Video: Senator Coons says Senator Harris will deliver tougher message to Trump

Then there are groceries. The price of a pound of ground beef has risen $1.05 since Biden took office, bringing the national average to $5.36 a pound, according to government data. Egg prices are still far lower than the highs they hit during the avian flu pandemic in late 2022, but at $2.72 a dozen they’re still 85% higher than three years ago. Chicken has risen 25% since January 2021, to $2.01 a pound.

But Biden administration economists calculate that average wages have risen enough to more than offset rising costs: As of June, the average hourly wage was 23% higher than it was four years ago, outpacing the 21% increase in average prices. As a result, White House economists calculate that it now takes a typical worker about 3.6 hours to buy a week’s worth of groceries, roughly the same as it did before the pandemic.

Economists say that after an inflationary surge, prices are not supposed to fall back to their previous levels. Such sustained price declines usually occur only during recessions. In a healthy economy, wages eventually rise enough to allow consumers to absorb the higher costs.

By some measures, lower-income workers fared especially well as employers have had difficulty filling many in-person jobs since the pandemic began. Wages for restaurant and hotel workers rose about 15% in the spring of 2022 from a year earlier, a rate that far outpaced inflation.

But household incomes overall have not risen as much as hourly wages, which can happen if fewer people in a household are working or if their working hours are cut.

Economists at Motio Research calculate that inflation-adjusted median household income has risen just 1.6%, to $79,000, since Biden took office in January 2021. (The median represents the middle value and excludes extremely high or low numbers that can skew the average.)

“When you see at least half of the population seeing their income stagnate for four years, it’s easy to understand why inflation is perceived as a big problem,” said Matthias Scaglione, co-founder of Motio.