Medal Table | Olympic Schedule | Olympic News

PARIS — Eight world-class swimmers glided through the pool in the men’s 100-meter breaststroke final at the 2024 Olympics on Sunday — none of them could have finished higher than eighth at the Tokyo Olympics three years ago.

In the previous night’s “Race of the Century,” the women’s 400-meter freestyle, all three former world record holders fell far short of their personal bests, with Katie Ledecky failing to even break four minutes.

After two raucous days of swimming at Paris’ La Défense arena, no new world records were broken, leading to whispers in the swimming community: is the pool the problem?

If so, many believe the specific problem lies in its depth.

World Aquatics, swimming’s world governing body, recommends that Olympic pools be three meters deep. The pool outside Paris, a temporary one installed in a rugby stadium similar to one built at Lucas Oil Stadium in Indianapolis for last month’s U.S. Olympic trials, is 2.15 meters deep. That’s above the two-meter minimum that was still in place when the Paris 2024 plans were approved but below World Aquatics’ new minimum standard of 2.5 meters.

A more specific problem is that in shallow pools, the water displaced by a swimmer can bounce back up at the bottom of the pool, creating a “wavy” or choppy condition in the last 50 metres of a 100 metre swim.

On the other hand, as the depth increases, the impact decreases. Some experts believe that the deeper the pool, the greater the performance.

These same people often describe shallow pools with an adjective that a layperson would never associate with a swimming pool: “slow.”

Some say that breaststroke in particular is susceptible to the effects of “wavy” turbulence.

Some believe the effect is so slight that it can be ignored: When asked in May about the difference between the 10-foot and 8-foot depths of U.S. Olympic qualifying pools, John Ireland, director of U.S. technical services for Myrta Pools, said, “It makes no difference.”

“It’s a question of perception versus reality,” he says. “If you talk to a lot of good coaches, they’ll tell you that a pool needs to be a minimum of three metres deep. Most of our research shows that anything over two metres is pointless. … Obviously some depth is very important, but beyond a certain point, there are diminishing returns.”

But without depth, what explains why no swimmer has ever broken 59 seconds in the 100-meter breaststroke final? (The world record is 56.88 seconds.)

Why was five of the seven races won by someone slower than the 2023 World Championship winner?

How do we explain why French phenom Leon Marchand, U.S. star Gretchen Walsh and dozens of other athletes failed to beat their personal bests?

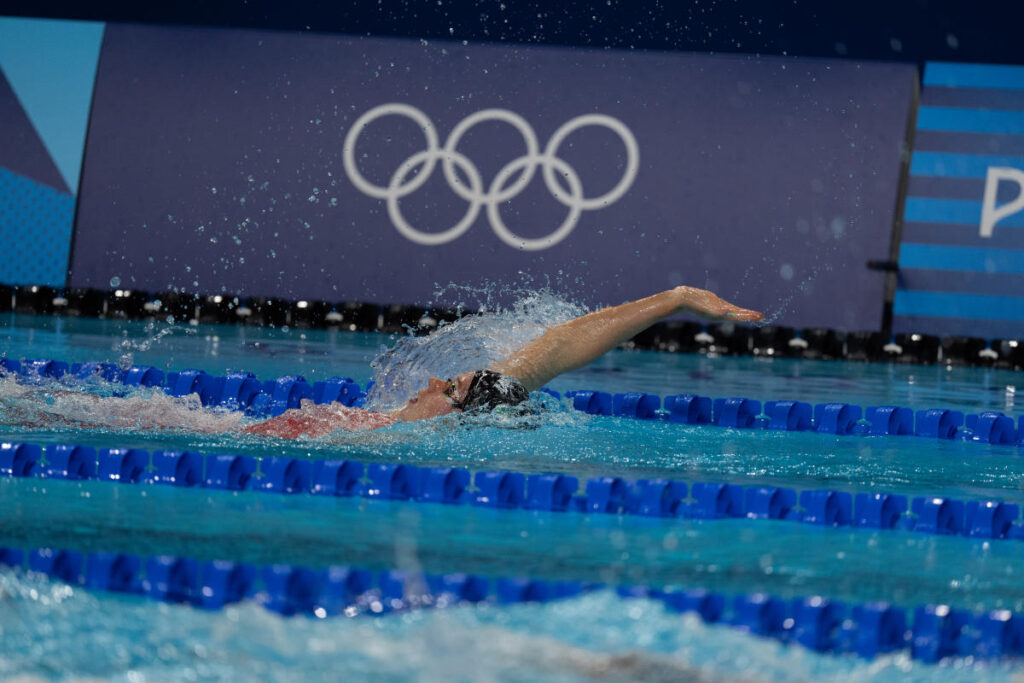

Italy’s Nicolo Martinenghi won the gold medal in the men’s 100-meter breaststroke in a time more than two seconds slower than the world record. (Associated Press/Martin Meissner)

“Not ideal for setting records”

Ken Ono, a data expert who works with US swimmers, echoes this general theory. “The pool is faster than the local swim club, but it’s not ideal for setting records,” he told Yahoo Sports in an email. “The shallow depth is the main reason, and I’ve heard from a few swimmers that it forced them to (slightly) modify their diving off the board.”

He declared and reiterated that “every aspect of the athletes’ performance was breathtaking,” but he speculated that “Would we have seen Marchand go under four minutes for the 400m individual medley or under 55 seconds for the 100m?” [Olympic champion Torri] Husk and Walsh? Honestly, that might have been the case in any other pool.”

Swimmers, too, spoke out about the slowness. “It was a strange one in terms of times,” Adam Peaty, Britain’s world record holder in the 100m breaststroke, said of the event.

“The times were not fast for anybody, and we talked about it with each other,” said Italy’s Nicolo Martinenghi, who beat Peaty to win gold in the 100-meter breaststroke final on Sunday, adding that he wasn’t sure why.

“But I don’t care,” he continued. “I’m the Olympic champion. I was the fastest today. That’s enough.”

Other athletes have adopted a similar attitude when asked about the quality of their pool. When asked, US freestyler Paige Madden initially laughed and replied, “Well… it’s hard to say, honestly. I think the results will become clear as the competition progresses.” More importantly, she added, “We’re all in the same boat. Times don’t matter. In the Olympics it’s all about placements.”

“I don’t know, a lot of people say they don’t like the feeling of the pool,” Katie Grimes said after her first swim on Monday morning. “Honestly, when I get in the pool, I don’t feel anything different. My times have dropped, but everyone’s in the same situation, so it doesn’t really matter.”

Several coaches and officials cautioned that the tournament is still early days, only two days into it. Reached by phone on Monday, Ireland also noted that “three Olympic records have been set in two days.” He said that Mirta, the industry leader who built the U.S. Trials pool and the Paris pool, “is pretty confident that this is a great example of an Olympic pool.” There’s no doubt that at some point the world record will be broken.

While the top times did not live up to expectations, on average, four of the seven finals so far have been faster than the equivalent races in Tokyo, and four of the seven have been faster than last summer’s world championships.

Given the broader advancements and accelerations in the sport known as “swim-flation,” one might expect six or seven of the seven to be faster.

But there were other factors that contributed to the relatively disappointing time: Walsh mentioned the “pressure” of living up to a world record; coaches said the venue could be “intimidating”; and the dozens of swimmers said it was the rowdiest atmosphere they’d ever experienced.

Then there are the external challenges that always complicate the Olympics but seem especially acute here in Paris: food complaints, doping tests, media liability, transport chaos. “Life in the Olympic Village makes it difficult to perform,” Australian athlete Ariarne Titmus said Sunday. “Obviously it’s not conducive to high performance.”

But the general consensus among athletes seems to be that this whole debate about “slow” pools is a bit silly.

“The pool is 50 meters and there are 10 lanes,” said Canada’s Summer McIntosh, the favorite to win Monday’s women’s 400-meter individual medley. “It’s an Olympic pool. I don’t think it should be said that all Olympic pools are slow pools. Whatever the pool, we’re all competing in the same pool. It doesn’t matter if it’s the fastest pool in the world or the slowest pool in the world. My goal is the same.”