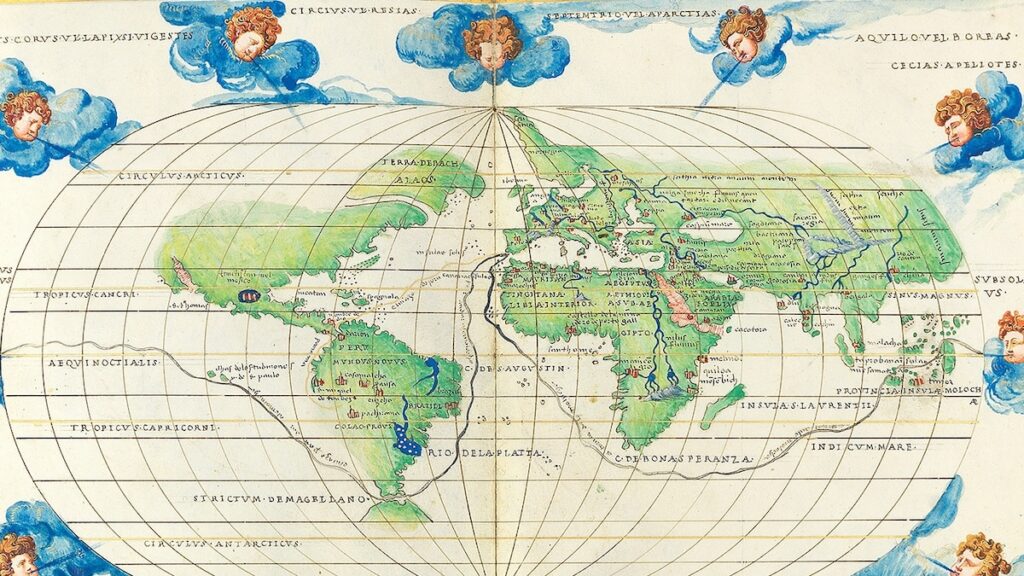

For centuries, humans have been fascinated by the mysteries of the Earth and the stars, and have documented their explorations in an incredible variety of ways. Egyptian scholar Claudius Ptolemy, known as the “inventor of geography,” revolutionized the field by recording latitude and longitude in the 2nd century AD, while Gerardus Mercator’s 16th century world projection remains influential today.

Maps from the Middle Ages (c. 500 to 1500 A.D.) were used less as aids to navigation and more as “visual summaries of all human knowledge,” says cartographer Peter Barber. While a modern viewer of maps might chuckle at historical inaccuracies, such as California being depicted as an island until the late 18th century, many of these ancient maps are filled with astonishingly precise detail.

Thanks to the newly launched online platform Oculi Mundi (Eye of the World), the public can now view these rare maps and atlases. Known as the Sunderland Collection, this treasure trove shows how European scholars meticulously represented the world from the 13th century to the early 1800s. The collection highlights the evolution of cartography and offers a window into the historical perspectives and artistic achievements of past civilizations.

Early mapping challenges

For a long time, people believed that the Earth was the fixed center of the universe, with the Sun and planets revolving around it, a theory put forward by Ptolemy. But a map created in 1532 by German scholar Sebastian Münster depicted a different idea, that an angel was using a lever to move the Earth.

(Here’s why your mental map of the world is (probably) wrong.)

Helen Sunderland-Cohen, curator of the Oculi Mundi collection, points out that the map’s unique depiction was both subtle and groundbreaking.[It] “The work would have been considered radical, perhaps heretical, when it was made,” she says.

Drawing the round shape of the Earth on a flat piece of paper presented a challenge to cartographers. To meet this challenge, Italian engraver Giovanni Cimerlino designed a heart-shaped map in 1566 that showed both the eastern and western halves of the world, including the Americas.

Giovanni Cimerlino’s 1566 heart-shaped (or cord-shaped) map is famous for its accurate depiction of the Americas.

Photo courtesy of the Sunderland Collection

Until 1660, the idea that the planets orbit the Sun (known as heliocentrism) remained controversial, despite now being understood to be correct. Andreas Cellarius’s Celestial Atlas is considered one of the greatest atlases ever made, demonstrating the sophisticated and daring efforts of early cartographers to represent the universe.

Revolutionary Contributions of Early Geographers

Maps of the past often reflected the cultural and political biases of their creators. Maps were not just tools of navigation, but also tools of power, propaganda, and education. For example, maps might exaggerate the extent of a ruler’s territory or highlight certain trade routes to assert dominance and influence.

(These legendary “ghost” islands only exist in the atlas.)

One of the most important explorations of the era covered by Oculi Mundi was Christopher Columbus’ voyage to the Americas in 1492. One of the maps, part of cartographer Johannes Ruysch’s Ptolemy Atlas, calls South America “Terra Sancta Crucis sive Mundus Novus” (Land of the Holy Cross, or New World). It is one of the oldest printed maps of the Americas.

While the map isn’t entirely accurate by modern standards, Barbour says it captures “the excitement of discovery and the bewilderment of people trying to assess what things are.”

Another notable map is the hand-coloured world map by Flemish cartographer Abraham Ortelius from 1603. “This was the first atlas in the modern sense and a pretty big step towards getting things ‘right’ geographically. This atlas brings together everything around the world and lays it out in a systematic way, just as modern atlases do,” says Sunderland-Cohen.

This atlas is significant because it was the first modern atlas to provide a systematic presentation of the world as we know it today. Ortelius’ map is also significant because it includes a fictitious continent believed to exist in the Southern Hemisphere, “Terra Australis nondum cognita” (Unknown Southern Lands).

Abraham Ortelius’ 16th-century Theatrum Orbis Terrarum was the first modern atlas, providing the most comprehensive representation of the then known world.

Photo courtesy of the Sunderland Collection

Matthew Edney, a professor of cartographic history at the University of Southern Maine, says Ortelius’ map reflects existing beliefs about the southern continent at the time. Europeans began exploring Australia in the early 17th century, but it wasn’t until the 19th century that ships became strong enough to approach the Antarctic. Edney says this depiction of the vast southern landmass “is not an error, it’s a history of trying to understand the world.”

Evolution of Geography

Sunderland-Cohen says that to understand the accuracy of historical maps, one must consider their context: “In some cases, it’s not that the map itself is wrong, it’s just that the map is presenting and trying to represent a large geographic area or concept.”

Scholars and cartographers would often emphasize certain features based on the information they had: for example, if a scholar had extensive knowledge of a particular trade route, that route would be featured prominently on the map.

“Most new geographic features are first introduced on one cartographer’s map, and then other people look at it and decide whether they trust the source and the depiction and want to include it on their own maps,” says Catherine Parker, map collections manager at the Royal Geographical Society.

(This map of Europe sparked a boom in playful cartography 500 years ago.)

Historical maps often included distinctive elements such as wind heads, a depiction of a human face with puffed cheeks to represent wind direction. These were decorative as well as functional for maritime navigation. Over time, maps also began to incorporate allegorical scenes, such as paintings of the seasons.

In some ways, Barber says, the representation of the map will never be perfectly accurate due to the inherent difficulties of mapping a spherical world on a flat surface. “You have to make compromises because flat paper doesn’t tell the whole truth,” he says. “And those compromises depend a lot on what you consider important.”