More than 800 inmates at Jaw Prison, Bahrain’s largest detention facility, went on hunger strike in August and September 2023 to protest poor conditions and the denial of proper medical care by the Bahraini authorities. Many of the hunger strikers had been unjustly detained following apparently unfair trials.

Ten opposition leaders remain imprisoned for more than a decade for their role in the 2011 pro-democracy movement. They include Hassan Mushaimah, leader of the unrecognized opposition group Al-Haq, opposition leader Abdulwahab Hussein, prominent human rights activist Abdulhadi Al-Khawaja, and Al-Haq spokesman Dr. Abduljalil Al-Singaseh. All four are serving life sentences after apparently unfair trials. Messrs. Al-Khawaja and Al-Singaseh remain without access to adequate medical care.

On March 8, Bahraini authorities revoked entry visas issued to two Human Rights Watch staff members to attend the 146th session of the Inter-Parliamentary Union (IPU) on January 30, 2023. Human Rights Watch has permanent observer status at the IPU, granting it access to the parliamentary body’s plenary sessions, but no senior IPU official has publicly criticized this.

Closure of political space, freedom of assembly, freedom of association

The Bahraini government continues to impose restrictions on expression, assembly and association; elections are not free or fair; and opposition voices are systematically excluded and suppressed.

Many members of Bahrain’s opposition parties, activists, bloggers and human rights defenders remain imprisoned for their roles in the 2011 pro-democracy movement and more recent political activism. They have been subjected to brutal treatment, including torture and denial of medical care. The authorities have failed to hold officials accountable for torture and ill-treatment in their custody.

In a joint letter to IPU delegates on March 6, Human Rights Watch, along with other human rights groups, highlighted human rights violations in Bahrain, urged them not to use the conference to express concern about the serious human rights violations in Bahrain, and urged them not to use the conference to whitewash Bahrain’s dismal human rights record.

Bahrain’s “political isolation laws,” introduced in 2018, barred former members of the country’s opposition parties from running for parliament or serving on the boards of directors of private organizations. These laws also target former prisoners, including those detained for political activities. Those affected by these laws routinely experience delays and denials in their applications for good conduct certificates, which are required for Bahraini citizens and residents to apply for jobs, enter universities, and even join sports and social clubs.

Two former Bahraini members of parliament have been jailed for exercising freedom of expression, and the government has expelled many more and stripped them of their citizenship.

Bahrain has had no independent media presence since the Ministry of Information suspended the country’s only independent newspaper, Al-Wasat, in 2017. Foreign journalists have little access to the country, and Human Rights Watch and other international human rights groups are routinely denied entry.

Death Penalty

Six people have been executed in Bahrain since 2017. As of September 2023, there are 26 people on death row who have exhausted their appeals. Bahraini courts convict and sentence defendants to death in demonstrably unfair trials based solely or primarily on confessions allegedly coerced through torture and ill-treatment.

Human Rights Watch and the Bahrain Institute for Rights and Democracy (BIRD) reviewed the cases of eight men facing death sentences, relying primarily on trial records and other official documents. The defendants were convicted and sentenced after manifestly unfair trials that were based primarily, or in some cases entirely, on coerced confessions. The trial and appeals courts in these cases rejected credible allegations of torture during interrogations, relied on secretly obtained documents, and denied or failed to protect fundamental rights to a fair trial and due process, such as the right to counsel during interrogations and the right to cross-examine prosecution witnesses. Bahraini authorities also violated their obligations to investigate allegations of torture and ill-treatment.

Religious Freedom

Bahrain’s government has a long history of discriminating against its Shiite majority population, including targeting Shiite clerics and arresting and prosecuting Shiite human rights activists, including Abdulhadi Al-Khawaja in 2011. UN experts have expressed concern that members of the Shiite community are being “targeted explicitly on the basis of their religion.”

In June Bahraini authorities imposed restrictions and checkpoints in and around Al-Diraz village, home to Imam Al-Sadeq Mosque, the main mosque for Bahrain’s Shia community, preventing worshippers from attending Friday prayers. The restrictions on access followed the brief detention by Bahraini authorities of prominent Shia cleric Sheikh Mohammed Sankour, who frequently preached at Imam Al-Sadeq Mosque.

Women’s Rights

The 2017 Uniform Family Code requires women to obey their husbands and not leave the marital home without a “good reason.” If a woman is deemed disobedient or rebellious by the courts, she may lose her right to spousal support (nafaka) from her husband.

Women cannot be guardians of children, even if the child’s father is deceased or if a court orders the child to live primarily with the mother after divorce. The 1963 Citizenship Act prohibits women from conferring citizenship on children of fathers other than Bahraini. Women have had difficulty obtaining passports for their children, especially if the child’s father is overseas.

Women also face discrimination in practice: at some universities, women may need parental consent to live in on-campus accommodation.

In February, the UN Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women released the findings of its investigation into women’s rights in Bahrain, which included concerns about “the narrowing of the space for women human rights defenders to work, and reports of retaliatory acts against women human rights defenders, including threats, harassment, intimidation, physical abuse, sexual violence, travel bans, and arbitrary detention.” The committee also noted the absence of a deadline for adopting amendments to the penal code to eliminate immunity from criminal liability when perpetrators of rape marry their victims.

Bahrain’s parliament has voted to repeal a law that exempts rapists from punishment if they marry their victims.

Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity

While there are no laws that explicitly criminalize same-sex relations, authorities have used vague criminal code provisions banning “indecency” and “immorality” to target sexual and gender minorities.

Migrant Workers

In Bahrain, the kafala (sponsorship) system that ties migrant workers’ visas to their employers remains in place, and leaving an employer without the employer’s consent can result in loss of residency and lead to arrest, fines, and deportation for “absconding.” In 2009, Bahrain allowed migrant workers to terminate their employment contracts after one year with their first employer by giving the employer reasonable notice (at least 30 days). However, in January 2022, parliament voted to extend this to two years. In addition, workers must pay the cost of a two-year work permit, but this is rarely used because it is too burdensome for many.

Bahrain’s labour law includes domestic workers but excludes them from some protections, such as weekly holidays, minimum wages and limits on working hours.

Online Surveillance and Censorship

Bahraini authorities continued to block websites and enforce the removal of online content, particularly social media posts critical of the government. Social media remains an important forum for activists and dissidents, but self-censorship is high due to fear of online surveillance and intimidation by authorities.

In March 2023, Bahraini authorities arrested four men over social media posts. One of the four arrested, Ebrahim Al Mannai, is a lawyer and prominent activist. post He told X, formerly known as Twitter, that the Bahraini government should reform its parliament if it wants it to stand out to the world.

Bahrain has purchased and used spyware, including NSO Group’s Pegasus spyware, to target government critics and human rights defenders.

Key international actors

In September 2023, Bahrain’s Crown Prince and Prime Minister Salman bin Hamad Al Khalifa visited Washington DC and signed the Comprehensive Security, Integration and Prosperity Agreement (C-SIPA), which aims to strengthen cooperation between the two countries in various areas, including defense, security, trade, investment, and emerging technologies. The agreement was signed shortly after several human rights groups called on the White House to use diplomatic ties with Bahrain to lobby for the release of Abdulhadi Al Khawaja.

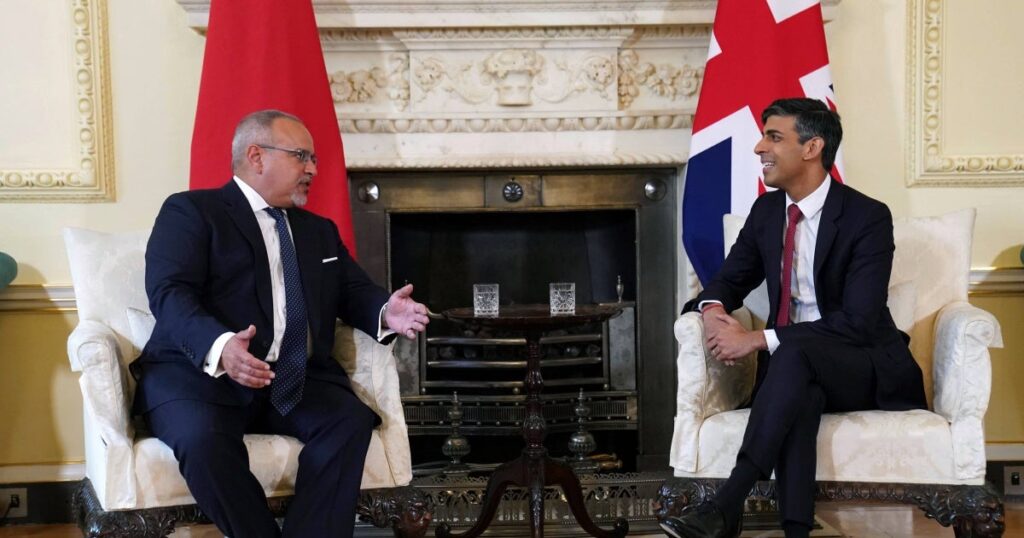

In July, the British Prime Minister hosted the Crown Prince to sign a Strategic Investment Cooperation Partnership, which “aims to drive over £1 billion of additional investment into the UK.” Through the Gulf Strategic Fund (GSF), the British government continues to fund Bahrain-led reform and capacity-building programs for institutions implicated in gross human rights violations. The GSF has supported the Bahraini Ministry of Interior and its ombudsman, special investigative unit and security agencies implicated in the abuse of at least eight men currently on death row.

In February, Human Rights Watch and other human rights organisations published a joint statement in response to the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office’s (FCDO) Human Rights and Democracy Report 2021, in which the UK government gave full praise to Bahrain’s restorative justice law for children as a “progressive step”, but failed to acknowledge that the law fails to protect key rights listed in the Convention on the Rights of the Child.